Does Inequality Cause (or Reduce) Crime? Does Poverty Cause Crime? Does investing in education reduce crime? What does reduce crime?

It is often argued that inequality or poverty causes crime, and that only by addressing these “root causes” can we reduce crime. For example, a Bloomberg View article tells us “Want to Fight Crime? Address Economic Inequality”:

Equally decisive in determining crime rates are the more invisible barriers to crime set up by social norms and social cohesion. Indeed, one of the most robust statistical patterns known is that crime rates tend to go up with rising economic inequality, which itself tends to go along with erosion of social trust….In a brilliant 2009 book titled “The Spirit Level,” researchers Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett reviewed hundreds of earlier studies and presented overwhelming evidence that economic inequality correlates directly with levels of crime and many other measures of social dysfunction. Nations with lower inequality have higher life expectancies, fewer homicides, lower infant mortality, higher levels of trust, and less obesity and addiction.

We can find similar writings in the NY Times, The Atlantic, World Bank, etc.

But as we know from Statistics 101, correlation does not prove causation. There are numerous variables that differ between countries or states that can have a correlated impact on inequality and crime: governance, ethnicity, culture, institutions, traditions, etc.

To avoid these confounders, another way to test the link between inequality and crime is to examine the treatment effect. If public policy choices increase inequality, does crime go up? If public policy choices decrease inequality, does crime go down?

From 1910 until the late 1970s, both England and America undertook concerted programs to reduce inequality. Both introduced progressive income taxes. Both changed laws to support unionization. And then in the 1980s both countries reversed course. Britain elected Thatcher, the U.S. elected Reagan. They lowered tax rates, made life more difficult for unions, and promoted business. Inequality rose in both countries for the next few decades.

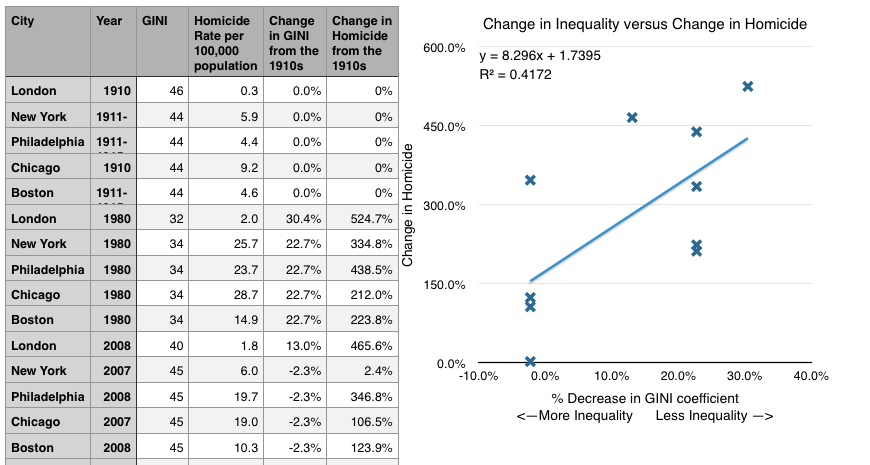

I’m going to restrict the analysis to the largest cities in England and America as of 1910, in order to help isolate confounding changes such as changes in urbanization, (and also because I don’t trust homicide numbers from rural areas from the 1910s). My measure of inequality will be the GINI coeffecient at the national level (since we do not have the GINI coefficient broken down at a local level). A higher GINI coefficient means more inequality.

Here is a plot of the change in homicide from the initial time period (the 1910s), to the peak of equality (~1980) and then to a new high in inequality (~2008):

Turns out that inequality reduces crime, and equality increases crime. For every 10% decline in inequality according GINI coeffecient, homicide nearly doubles! That is a very strong correlation. (You can download my spreadsheet here).

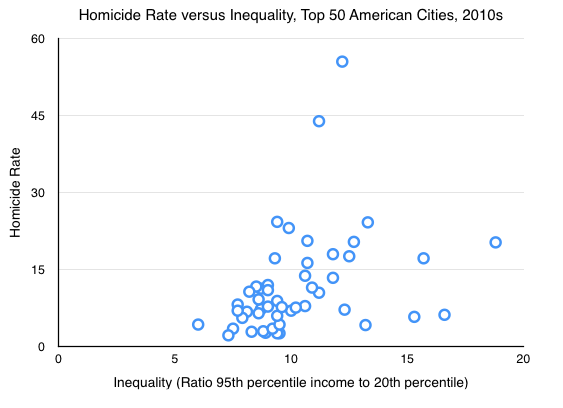

We should cut the data another way in order to confirm these findings. My measure of inequality for cities was crude because I used a single American number for all American cities, since that is all the data I had for 1910 and 1980. But in recent years we have data that allows us to breakdown inequality by individual city in America. Here are the same four cities, showing inequality to homicide in 2012. Again, more inequality means less homicide:

Clearly this is an open and shut case. Inequality reduces homicide. We should give more tax cuts for the rich and cut the minimum wage.

Now…do I actually believe this? No. My results above are due to tricks and confounding factors.

First, I cherry-picked my data set. I left out the 1920s (which in America had rising inequality due to the roaring 20s and rising homicide due to prohibition). I omitted the 1950s which had low inequality and low crime.

Second, with regards to the United States, I chose specific cities that were impacted by the Great Migration. The homicide increase in Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia were in part a straightforward result of demographic changes. An ethnic group with historically much higher crime rates moved into those cities. If more of a city is composed from a higher crime rate population, then mathematically, the homicide rate of the whole goes up, even if there has been no behavioral change within each group.

Third, another confounder is correlated public policy. When liberals were in power, they enacted policies that both reduced inequality and relaxed law enforcement (in the U.S. for instance, imprisonment per buglarly offence dropped by 75% during the 1960s). Then in the 1980s there was a backlash and we had multiple decades of pro-capitalism, tough-on-crime leaders: Thatcher, Reagan, Clinton, Blair. It likely wasn’t the equality that caused the crime – it was the other policies that went into effect at the same time.

Fourth, with regards to the city level data, there is a composition effect. Upper classes commit less crime, the underclass commits more crime. If in a particular city underclass violence causes the upper class to move out, overall equality within the city limits will rise. The violence will have caused equality. Or, if a city has an influx of wealth, the newly enriched upper class can price out the underclass. An economic boom can thus cause more inequality and less homicide within the city limits.1

Note that these confounding variables can cause correlations in the opposite direction based on circumstances. For instance, with regards to public policy, corrupt, incompetent governance can cause both higher crime and more inequality. And with regards to demographic composition, if a nation has an influx of an underclass population, that can also cause a correlated increase in crime and inequality.

In total, the statisical analysis above does not prove causation. But – all those studies using correlations to show the opposite, that inequality causes crime, are also bogus. They are also cherry-picked, confounded, and intellectually dishonest. With so many interlocking causal factors, anyone who calculates a correlation with regards to inequality and crime and tells you this proves X causes Y is either appallingly stupid or utterly mendacious.

So now that I have muddied the waters so much – what do I actually think about the link between inequality or poverty and crime?

The idea that a nation’s level of statistical inequality, in and of itself, causes homicide, stikes me as absurd from a common sense standpoint. If there is a boom in Silicon Valley and tech entrepreneurs make billions, driving up inequality, then people in Boston or Detroit or Baltimore are more likely to shoot each other? That does not make sense.

At a local or personal level, I am also dubious of the idea that inequality causes crime. There are countless examples of people living just peacefully in the face of massive inequality, for example: Microsoft interns attending a party at Bill Gate’s house; the broke college athletes playing hard for millionaire coaches; the low-paid janitors and dishwashers of every rich American city who don’t kill their rich clientele; the working class deferring to the upper classes in Edwardian England; all the slaves who did not kill their master’s wife when their husbands were away fighting the Civil War. Furthermore, when we look at high-crime areas, very little of the crime is committed by the poor against the rich. Most of it is beefs and vendettas against equals. Perceived unfair inequality can cause resentment, but even this rarely leads to crime, and certainly does not explain crime committed within a community of equally poor people.

And while statistical correlations cannot prove causation, the data does show that these confounding variables are far, far, far more important than inequality. If one of the most unequal societies (1910’s England) had one of the lowest crime rates in Anglo-American history, then clearly inequality is not determinative. Clearly, we can solve the problem of crime without solving the problem of inequality, because we have done so before. And on the flip side, there is no evidence that we can solve crime by reducing inequality, because we have never done so before.

The link between poverty and crime is a bit more complicated. Within a given time and place, it is clear that poverty is correlated with crime. On the other hand, London of the 1910s or Philadelphia of the 1910s was not only more unequal, but much poorer. The lower classes suffered a level of material deprivation and hunger that is very rare even in the poorest modern American ghettos2. If poverty is a definitive, “root cause” of crime, the crime rates should have been much higher then, not much lower. Worldwide, there are many places much poorer in the material sense than American ghettos, while having much lower crime rates. Clearly then, poverty does not inevitably lead to crime. Rather, I think the obvious explanation is that other factors cause both crime and poverty:

First, the inherent personality qualities that make one more likely to commit homicide (impulsiveness, prone to rage, not thinking about long term consequences, disobedience to authority) also make it harder for that person to hold down a good job. Poor personal character can cause both crime and poverty.

Second, the qualities that make a community more violent also make it poorer (break down in law and order, bad government, brain drain, lack of strong competent authority figures, a population that doesn’t plan for the future). So again, societal breakdown can cause both crime and poverty.

Third, underclass populations are often stuck in an equilibrium where “respectability” is not needed. Or they are stuck in a “vendetta” or “honor culture” equiilbrium where a reputation for violence is actively cultivated. This classic essay on riots phrases things well:

Respectability—a reputation for behaving in a predictable, socially benign manner—is an extremely valuable asset for most people who live in the middle class world. It is one of the key ingredients in career and personal success, and the need for it serves as a sort of performance bond to keep middle class people in line. A person to whom respectability matters much should demand better odds before risking arrest and disgrace than would a football hooligan or a member of the American urban underclass or any other socially marginal character to whom respectability is of relatively little value. Such a person has something that a middle class person lacks—a great deal of nihilistic freedom of the “nothing to lose” variety. Such freedom, experience suggests, is a perplexing and often malignant possession. Any social policy that would materially improve the life chances of a potential rioter would concurrently raise the value of respectability to such a person, and thus dampen the incentive to participate in civil disorders.

This is not to suggest that reputation matters less to a hooligan than it does to an orthodontist. The question is, reputation for what. A valuable reputation among the thugs is a reputation for hard partying, physical toughness, “sticking by your mates,” and above all an ability to engage in predatory behavior without being arrested.

….Reducing these individuals’ disposition to violence would seem, therefore, to involve getting them to identify with the larger community—making them middle class, in other words. Alas, that is easier said than done.

Note that this lack of care about “respectability” is not an inevitable aspect of poor communities. From my reading of history, many of our grand-parents cared more about respectability despite being materially worse off. Compare this depression-era bread-line to the dress of a modern IT professional. The poor often rely more on charity from neighbors and on credit from the local shopkeeper. This can mean they have an extra incentive to maintain good behavior. They are often one slip-up away from losing a job and going hungry, which means extra incentive to be well-behaved at work.

In some times and places the peasant poor are the most respectable, and it is the nobles who are the worst behaved (because their status makes them immune to censure and punishment). As historian Peter Turchin noted:

A murder was followed by revenge in a cycle of violence familiar to fans of Mafia crime stories. Moreover, frequent and brutal assaults and homicides undermined the social and psychological barriers against interpersonal violence. It was really the nobles who were the “criminal underclass” during the late Middle Ages.

Similar stories of violent upper classes can be told elsewhere. Historian William Durant writes that in the 1560’s Germany people used to fear the (higher class) college students: “In most university towns the citizens hesitated to go out at night for fear of the students, who on some occasions attacked them with open knives.” British aristocrats had the Hellfire Club. In modern America we have our rowdy and decadent frat bros. In pre-modern Japan, Fukuzawa writes of the young samurai students in Osaka scaring the townspeople off the street for fun (there were no police at the time holding the samurai accountable to the law).

The only plausible theory for a causal relationship between reducing poverty and reducing crime is that poor people have nothing to lose. If you give them money, they will have something to lose, and thus will be less willing to take risks and commit crime. However this logic ignores that even very poor people can be incentivized not to take risks – even a poor person does not want to have their freedom taken away or to face corporal punishment. And giving poor people money so that “they have something to lose” only works in reducing crime if you actually take away the money if they misbehave – which is something the American welfare state has routinely failed to do. If you simply give the poor money and housing, without any strings attached, you will essentially turn them into a sort of debased nobility. Bad behavior will not result in consequences, and so behavior will become worse.

Social Differences between High-Crime Poor Communities and Low-Crime Poor Communities

To learn about the actual causes and cures for crime, we must go beyond statistics and read actual accounts of high-crime and low-crime poor communities.

For the low-crime community, we’ll turn to Robert Roberts’ book The Classic Slum: Salford Life in the First Quarter of the Century . He describes growing up in one of the poorest sections of England around 1910. In his account we see great material hardship, great inequality, but none of the problems of homicide, predatory assault, robbery, or single motherhood that plague the modern American ghetto and the council housing in Britain. While there had been problems of gangs of “scuttlers” and highway men in the 1800s, those problems had been largely surpressed by 1910. The homicide rate for London was around .5 per 100,000 – ten times less than the homicide rate in modern America. I cannot find the murder rate for Salford or Manchester specifically back then, but Roberts never mentions any murders or predatory crimes in his book, nor even the fear of such crime, so we have no reason to think that his slum is more dangerous than the statistics indicate. If poverty or inequality causes crime – why does one of the poorest and most unequal slums in Anglo-American history exhibit the lowest levels of crime in Anglo-American history?

The community faced a high degree of poverty and hunger, to a degree much worse than is found in the poor areas of modern cities:

One saw a quarter of a class sixty ‘strong’ come to school barefoot. Many had rickets, bow legs or suffered from open sores….

…What ‘luxuries’ people bought at a corner shop often figured only in the father’s diet, and his alone. ‘Relishes’ consisted of brawn, corned beef, boiled mutton, cheese, bacon (as little as two ounces of all these), eggs, saveloys, tripe, pigs’ trotters, sausage, cow heels, herrings, bloaters and kippers or ‘digbies’ and finnan haddock. Most could be bought from the corner shop. These were the protein foods vital to sustain a man arriving home at night, worked often to near-exhaustion. When funds were low a pennyworth of ‘parings’, bits from a tripe shop (sold by the handful in newspaper), staved off hunger in many a family. Another meal in such times, long known and appreciated, was ‘brewis’. It consisted merely of a ‘shive’ of bread and salted dripping broken up and covered with boiling water.

…

… Dining precedence in the homes of the poor had its roots in household economics: a mother needed to exercise strict control over who got which foods and in what quantity. Father ate his fill first, to ‘keep his strength up’, though naturally the cost of protein limited his intake of meats. He dined in single state or perhaps with his wife. Wage-earning youth might take the next sitting, while the younger end watched, anxious that any titbit should not have disappeared before their turn came. Sometimes all the children ate together: a basic ration of, say, two slices (and no more) of bread and margarine being doled out.

Because of the lack of class mobility, people of ambition character and intelligence tended to remain in the community:

Before 1914 the proletariat contained, far more than it does today, many men and women of personality, character and high intelligence, who were chained socially and economically within their own society. Such people in a more equitable system would, of course, have found a place far more fitted to their abilities: but only a very few, aided by luck and determination, succeeded in breaking through their environment. The vast majority, half conscious often of talents wasted, felt a frustration they could hardly have explained.

The community was tight-knit, with knowledge of deeds and misdeeds spreading quickly:

OVER our community the matriarchs stood guardians, but not creators, of the group conscience and as such possessed a sense of social propriety as developed and unerring as any clique of Edwardian dowagers….Over a period the health, honesty, conduct, history and connections of everyone in the neighbourhood would be examined. Each would be criticized, praised, censured openly or by hint and finally allotted by tacit consent a position on the social scale. Misdeeds of mean, cruel or dissolute neighbours were mulled over and penalties unconsciously fixed. These could range from the matronly snub to the smashing of the guilty party’s windows, or even a public beating. The plight of the aged, those without shelter or reaching near-starvation would be considered and their travail eased at least temporarily by some individual or combined act of charity.

The poor certainly helped the poor. Many kindly families little better off than most came to the aid of neighbours in need without thought of reward, here or hereafter. They were the salt of the earth. We knew others, too, who in return for help exacted payment in fulsome gratitude. Again, not all assistance sprang from the heart: in a hard world one never knew what blows fate would deal; a little generosity among the distressed now could act as a form of social insurance against the future.

…

Drunkenness, rowing or fighting in the streets, except perhaps at weddings and funerals (when old scores were often paid off), Christmas or bank holidays could leave a stigma on a family already registered as ‘decent’ for a long time afterwards. Another household, for all its clean curtains and impeccable conduct, would remain uneasily aware that its rating had slumped since Grandma died in the workhouse or Cousin Alf did time. Still another family would be scorned loudly in a drunken tiff for marrying off its daughter to some ‘low Mick from the Bog’.

On the whole, though, most families were well aware of their position within the community, and that without any explicit analyses. Many households strove by word, conduct and the acquisition of objects to enhance the family image and in so doing often overgraded themselves. Meanwhile their neighbours (acting in the same manner on their own behalf) tended to depreciate the pretensions of families around, allotting them a place in the register lower than that which, their rivals felt, connections, calling or possessions merited.

Reputation and the fear of losing status had a great impact on behavior:

Mothers round washing lines or going to the shop half a dozen times a day would inevitably hear of the peccadilloes of their offspring. Punishment followed, often unjustly, since the word of an adult was accepted almost always against that of a child. With some people a child had no ‘word’; only too often he was looked upon as an incomplete human being whose opinions and feelings were of little or no account – until he began to earn money! It is true that a much more indulgent attitude towards the young had already developed among the middle classes, but it had not yet spread far down the social scale. In the lower working class ‘manners’ were imposed upon children with the firmest hand: adults recognized that if anything was to be got from ‘above’ one should learn early to ask for it with a proper measure of humble politeness. There was besides, of course, the desire to imitate one’s betters.

…

If a single girl had a baby she lowered of course not only the social standing of her family but, in some degree, that of all her relations, in a chain reaction of shame. Strangely enough, those who dwelt together unmarried – ‘livin’ tally’ or ‘over t’ brush’, as the sayings went – came in for little criticism, though naturally everybody knew who was or who was not legitimate.

One of the reasons reputation mattered, was because if a family had trouble making ends meet, the first recourse was to seek credit from the shopkeeper. The credit given would depend on the person’s reputation:

And through those years (so beloved now by the elderly middle classes), and for long after, my mother kept shop among it all, noting what passed with a mixture of shrewdness and sardonic compassion. ‘In the hardest times’, she said, ‘it was often for me to decide who ate and who didn’t.’ If bankruptcy, always close in a slum corner shop, was to be avoided, one had to assess with careful judgement the honesty, class standing and financial resources of all tick customers. Not one but scores of families could lie in a poverty that left them with hardly any food at all. They appealed for credit. Then a shopkeeper’s generosity and humanity fought with his fears for self-preservation – to trust, or not to trust?

After closing time at 11 p.m. shop windows were covered with wooden shutters bolted together from within, this to discourage dangerous thoughts among those who stared in hungrily during the day. A wife (never a husband) would apply humbly for tick on behalf of her family. ‘Then, in our shop, my mother would make an anxious appraisal, economic and social – how many mouths had the woman to feed? Was the husband ailing? Tuberculosis in the house, perhaps. If TB took one it always claimed others; the breadwinner next time, maybe. Did the male partner drink heavily? Was he a bad time keeper at work? Did they patronize the pawnshop? If so, how far were they committed? Were their relations known good payers? And last, had they already ‘blued’ some other shop in the district, and for how much? After assessment credit would be granted and a credit limit fixed, at not more perhaps than five shillings’ worth of foodstuffs in any one week, with all ‘fancy’ provisions such as biscuits and boiled ham proscribed.

People worked hard because losing a job had very serious consequences:

So our neighbours, and many like them, in this ‘thrice happy first decade’ fought on grimly, certainly not to rise, but to stave off that dreaded descent into the social and economic depths. Under the common bustle crouched fear. In children – fear of parents, teachers, the Church, the police and authority of any sort; in adults – fear of petty chargehands, foremen, managers and employers of labour. Men harboured a dread of sickness, debt, loss of status; above all, of losing a job, which could bring all other evils fast in train. Most people in the undermass worked not, as is fondly asserted now, because they possessed an antique integrity which compelled ‘a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay’ (whatever that means); they toiled on through mortal fear of getting the sack. Fear was the leitmotif of their lives, dulled only now and then by the Dutch courage gained from drunkenness.

A craftsman thrown out of work sought another job at his ‘trades club’ or in a certain public house. If these failed him he began the weary round from firm to firm or from town to town, a journeyman in reality, asking for work. Building labourers I have seen as a child follow a wagon laden with bricks from the kilns, hoping to find a job where the load was tipped. For the same reason, too, they would send a wife or child trailing behind a lime cart. On some building sites a foreman might find fifty labourers pleading for a mere half-dozen jobs. It was not unknown for him to place six spades against a wall at one hundred yards’ distance. A wild, humiliating race followed; work went to those who succeeded in grabbing a spade.

In many firms and industries the battle for social justice still remained unjoined. There it was perilous for employees even to mention trade unionism. At the local dyeworks, in a meeting between masters and workers, one man had the temerity to say that since the employers had ‘combinations’ he saw no reason why workers should not have them too. The manager sacked him on the instant, in spite of his thirty years’ service, together with another who had called ‘Hear! Hear!’, and refused to pay them anything in lieu of a week’s notice.

If all else failed, a man would have to submit to the authority of a workhouse, where his life would be under tight control:

Seventy years before, when workhouses were established, it had been emphasized in a Bill which Parliament welcomed with enthusiasm that conditions of living in the ‘unions’ must deliberately be made ‘less eligible’ – that is, more wretched – than those suffered by the lowest-paid worker outside. As conscious policy, any entrant to the workhouse had to be openly humiliated, and this was done with such thorough, cold-hearted effect that it cowed the undermass for the better part of a century. The workhouse system meant, said one of its inspirers,

having all relief through the workhouse, making the workhouse an uninviting place of wholesome restraint, preventing any of its inmates from going out, or receiving visitors without a written note to that effect from one of the overseers, disallowing beer and tobacco and finding them work according to their ability: thus making the parish fund the last resource of a pauper, and rendering the person who administers the relief the hardest taskmaster and the worst paymaster that the idle and dissolute can apply to.

Parents were very authoritarian over their households:

In his book Exploring English Character Geoffrey Gorer shows with an abundance of statistical detail how, even in the 1950s, the corporal punishment of children still figured largely in English working-class homes. It seems certain that during the early years of this century the practice was much more widespread and severe. Because of it many children went in awe and fear, first of their parents, then of adults generally. Naturally, across the gulf, even in the strictest households, there could be much love and understanding for the young, and parents who rejected beating altogether. But no one who spent his childhood in the slums during those years will easily forget the regular and often brutal assaults on some children perpetrated in the name of discipline and often for the most venial offences.

…

Round parents the household revolved, and little could be done without their approval. Especially was paternal consent needed. In compensation, perhaps, for the slights of the outside world, a labourer often played king at home. Parents decreed on both one’s work and leisure and set standards of conduct, taste and culture even if they didn’t follow them. ‘As long as you have your feet under my table,’ a father would announce to one of his offspring, ‘it’s not do as I do, it’s do as I say!’ There were, of course, many working-class homes where music and literature had long held honoured place, but at the lower levels reading of any kind was often considered a frivolous occupation. ‘Put that book down!’ a mother would command her child, even in his free time, ‘and do something useful.’ Teenagers, especially girls, were kept on a very tight rein. Father fixed the number of evenings on which they could go out and required to know precisely where and with whom they had spent their leisure. He set, too, the exact hour of their return; few dared break the rule. One neighbour’s daughter, a girl of nineteen, was beaten for coming home ten minutes late after choir practice. Control could go on in some families for years after daughters had come of age. Such narrow prohibitions naturally led to much misery and frustration in the home, though there was a deal of conniving among the members of some families to help the young dodge the great man’s strictures.

And how effective were his vetoes? The number of illegitimate births in the period 1900– 10 was very small.

‘Dancing rooms’ being often taboo and visits to each other’s crowded kitchens impossible, youthful couples walked the streets or stood in dark doorways, often to be duly marked and reported on. One moralist in our neighbourhood with half a dozen convenient courting recesses round his warehouse, in order to forestall sin, kept them permanently daubed with sticky tar.

The class divisions in England of that time were stark and massive inequality was obvious. Roberts accounts a story that sounds like a scene from a Dicken’s novel:

Our school, lowest scholastically and socially of the three attached to its parish church, was ruled by the rector, a large man of infinite condescension. Once a week he called upon us, booming; the Head at sight of him seemed to shrink into a stoop of deference….

One bitterly cold autumn day we had no heat in school. As one of the more presentable boys in the class, I was dispatched by our headmaster with a letter to authority requesting that fires be lighted before the allotted date. Away I trotted in mid-morning across town to ring at the Rectory, a double-fronted villa deep in a garden. The maid let me in, took my note away and returned, beckoning across carpets – ‘The Breakfast Room!’ Awed, I followed a second servant bearing a tray into the aroma of coffee and cooked meats. The rector, wearing a red dressing gown, slouched side-on to a table, a newspaper spread, in an apartment warm, and dark with mahogany. He was holding my letter in his hand and looked at me over his glasses. Then he crumpled it and tossed it a yard across a thicket of fire-irons into blazing coals. ‘Very well!’ he grunted. ‘Just for the cold snap, tell him!’

I left overwhelmed. Such grandeur!

…

Nowhere, of course, stood class division more marked than in a full house at the theatre, with shopkeepers and publicans in the orchestra stalls and dress circle, artisans and regular workers in the pit stalls, and the low class and no class on the ‘top shelf’ or balcony. There in the gods hung a permanent smell of smoke from ‘thick twist’, oranges and unwashed humanity. Gazing happily down on their betters the mob sat once a week and took culture in the shape of ‘East Lynne’, ‘The Silver King’, ‘Pride of the Prairie’, ‘A Girl’s Crossroads’, ‘The Female Swindler’, ‘A Sister’s Sacrifice’ and the first rag-time shows.

The upper-classes condescended to the lower-classes, and this was met with a combination of deference, respect, and anger:

Parents saw their children’s teacher passing through the streets with a proper awe – a tribute which doubtless gave pleasure to the recipient and all his working-class relations. The school staff patronizing their flock were condescended to in turn by the rector, visiting clergy and His Majesty’s inspectors. Our headmaster, ever conscious of his standing, spoke politely to the mothers of his pupils whenever they called, timid and deferential, at the school. He cared about them and their children, ‘but’, complained the women in the shop, ‘he speaks to you like you was half-witted!’ In this the headmaster merely followed common practice. Many in the working class talking to their betters used their normal speech but aspirated most words beginning with a vowel in an effort to ‘talk proper’. This habit Punch found extremely funny. As a whole, the middle and upper classes, self-confident to arrogance, kept two modes of address for use among the poor: the first was a kindly, de haut en bas form in which each word, of usually one syllable, was clearly enunciated; the second had a loud, self-assured, hectoring note. Both seemed devised to ensure that though the hearer might be stupid he would know enough in general to defer at once to breeding and superiority. Hospital staff, doctors, judges, magistrates, officials and the clergy were experts at this kind of social intimidation; the trade unionist in his apron facing a well-dressed employer knew it only too well. It was a tactic, conscious or not, that confused and ‘overfaced’ the simple and drove intelligent men and women in the working class to fury. Some middle-class women, impudent magistrates, prison governors, military and small public school types still exploit it.

The only hint of criminality in Roberts’ account of Salford is in his stories of street gangs. But by the 1900s these gangs had been tamed by ruthless police action. The remaining brawls was amongst themselves, and more equivalent to the a hard-fought, Friday night, tackle football game than the general predation of modern ghetto violence:

The groups of young men and youths who gathered at the end of most slum streets on fine evenings earned the condemnation of all respectable citizens. They were damned every summer by city magistrates and unceasingly harried by the police. In the late nineteenth century the Northern scuttler and his ‘moll’ had achieved a notoriety as widespread as that of any gangs in modern times. He too had his own style of dress – the union shirt, bell-bottomed trousers, the heavy leather belt, pricked out in fancy designs with the large steel buckle and the thick, iron-shod clogs. His girl friend commonly wore clogs and shawl and a skirt with vertical stripes. That fraternity of some thirty to forty teenagers who lived in the street where our Church of England school stood achieved such a fearsome reputation for gang battle that they were remembered by name in The Times seventy years after. By my youth most of these were married and worthy householders in the district. In many industrial cities of the late Victorian era and after, such groups became a minor menace. Deprived of all decent ways of spending their little leisure, they sought escape from tedium in bloody battles with belt and clog – street against street. The spectacle of two mobs rushing with wild howls into combat added still another horror to the ways of slumdom. Scuttlers appeared in droves before the courts, often to receive savage sentences. In the new century this mass brutality diminished somewhat, but street battles on a smaller scale continued to recur spasmodically in our district and in others similar until the early days of the first world war….All the warring gangs were known by a street name and fought, usually, by appointment – Next Friday, 8 p.m.: Hope Street v. Adelphi!

Now let us us compare Robert’s Classic Slum to the modern American ghetto. We’ll focus on the book American Millstone which is a compendium of Chicago Tribune articles written in the early 1980s about the Chicago ghetto. The story it relates is similar to other personal accounts, such as Gang Leader for a Day, David Simon’s The Corner, or Jill Levoy’s Ghettoside.

The neighborhood of interest in American Millstone – North Lawndale – had a homicide rate of 55 per 100,000. That is 100 times higher than the homicide rate in rate in London or of England of 1910s.

In recent years, the robbery rate in Chicago as a whole has been around 500-600 per 100,000. The robbery rate in London and Liverpool around 1915 was around 0.25. That is not a typo. Modern Chicago has 2,000 times as much robbery. The .25 per 100,000 figure for 1915s London was very low even compared to American cities during that time period. When the American social science Raymond Fosdick was compiling this data, he was so suprised by the robbery statistics that he added a footnote. “The astonishing discrepancy in these statistics led to a careful investigation….The fact remains that highway robberies or ”hold-ups“ do not occur in Great Britain with anything like the frequency they do in America.”

This is also corroborated by first hand accounts. For instance in the 1870s Luke Owen Pike wrote:

Meanwhile, it may with little fear of contradiction be asserted that there never was, in any nation of which we have a history, a time in which life and property were so secure as they are at present England. The sense of security is almost everywhere diffused, in town and country alike, and it is in marked contrast to the sense of insecurity which prevailed even at the beginning of the present century. There are, of course, in most great cities some quarters of evil repute, in which assault and robbery are now and again committed. There is, perhaps, to be found alingering and flickering tradition of the old sanctuaries and similar resorts. But any man of average stature and strength may wander about on foot and alone, at any hour of the day or the night, through the greatest of all cities and its suburbs, along the high roads, and through unfrequented country lanes, and never have so much as the thought of danger thrust upon him, unless he goes out of his way to court it.

I think we can say with confidence then, that the homicide and robbery rates in modern Chicago are multiple orders of magnitudes higher than those found in London during the 1910s.

Let us excerpt from American Millstone to see how their lived experience compares. We start with the account of Dorthy, a single-mom, the middle of three generations living on welfare:

But when she was 15, the same thing happened to her that had happened to her mother at the same early age: She became pregnant, her sexual interlude the product of a schoolgirl’s crush. “I was tired of taking care of children,” Dorothy remembers. “I didn’t want a child.” When her mother found out, she did not hit her daughter, as Dorothy had feared she might. She cried.

Dorothy dropped out of school to have her first baby, Barbara. Like her mother, she signed up for public aid. Her first check, she remembers clearly, was for $23.

Dorothy began taking birth-control pills, not wanting more children. But she did not understand how they worked, swallowing one before each act of intercourse. After the birth of her second daughter, Dorothy asked doctors to tie her tubes. They refused, saying they could not perform such an operation because she was not married and not yet 21. (page 22)

…

[Dorthy met a carpenter who became a live-in boyfriend] With Little in the home, some of the burden was taken off Dorothy. He liked to roughhouse with the children and watched them from time to time. But the environment was tumultuous. Like her mother, who now is dead, Dorthy put up with a lot from her man-drinking, beatings and philandering. One night after he came home drunk and began pummeling her face, she considered leaving. Instead, she grabbed a telephone and slammed it against his head and decided to stay.

Whatever stability the family had when Little was alive seemed to disintegrate when he died. The children became hard to handle. Nothing seemed to get done unless Domthy yelled and “whupped” and yelled again. She married a man “just because he asked me,” only to separate five months later. There was so much chaos in the household that Dorothy’s oldest daughter, Barbara, was seven months along before Dorothy noticed that she, just like her mother and her grandmother before, was pregnant at 15.

When he heads off for school in the morning, [her son] William says, he sometimes feels as though he should just keep walking and never come back home. He knows something is wrong. To get pocket change, he admits to having bullied neighborhood kids for “protection money,” and he hops turnstiles at the “L” stations for a free ride when he is broke. Most of the time, he says, he feels angry.

Sean is the one who gives Dorothy the most concern. “He is vulnerable,” she explains, “and he likes money too much.” The 11-year-old flunked 2nd and 5th grades and has started to draw street gang graffiti on his clothes and arms. He fights. “If the price was right,” Dorothy says, “I wouldn’t be surprised if he could be persuaded to sell drugs.”

While women in the Salford slums were under the strict authority of their mother and father, who could supervise the courtship process, Dorthy had to fend for herself in her romantic relationships. And then, without a father in the house, the next generation of children went unsupervised as they bullied other kids and got involved with gangs.

In Salford, for an able-body man to go on relief would require entering a workhouse where he would lose all access to sex and alcohol. But in the case of Calvin Barret in Chicago his government check came with no strings attached:

By the time Calvin Barrett leaves the apartment, it is past 10 a.m. Adusting the tilt of his black cloth cap, he bids goodbye to the person he calls his “woman” and struts through the fircnt door, out onto the sidewalk and into what has become his daily routine.

Barrett is 36 and an ex-convict, released from Stateville Penitentiary in 1981 after doing two years for burglary. After a couple of months on the street, he committed another burglary and was sent back to prison.

Today the taxpayers are paying for his liquor.

Like 5,034 others in this community, Calvin Barrett derives part of his income from general assistance, the welfare program for single men and women with no dependent children. He receives a monthly check for $151.55, plus $79 in food stamps, which he can sometimes sell for a little more than their cash value

In Salford, all of the youth were raised from a little child to have respect for adults. And the word of an adult is always taken over. If youth committed even a minor offense, they would be reported to their father, who would give the youth suitable punishment. In Chicago, the worst element among the youth openly preyed open the old:

Everyone in the ghetto is afraid. “Every day, it’s constantly on their minds, the fear of being hurt,” Father Clements says’

For example, Sister Jean Juliano, one of several Daughters of Charity who work at Marillac House, n22W. Jackson Blvd., on the West Side, notes: “There is a general fear on the part of seniors to come out on the streets, especially on the lst and 3d of the month when their checks come in.”

“They know there are young punks waiting to knock them down and take their wallet or purse. They’re afraid to death to open their doors, especially at night. They have become prisoners in their own homes.”

“The young punks around here have no respect for anyone. They’d cut their own grandmother’s throat.”

American Millstone (p. 43)

Punishment was also less serious in Chicago, as compared to in England where a predatory robbery could easily bring the death penalty:

Winston Moore, the Chicago Housing Authority security chief, blames the increase in inner-city drug use and the increasingly violent nature of underclass crime on the white and black middle classes, which have been indifferent toward ghetto crime and lenient toward ghetto criminals.

“There’s no justice when poor people commit crimes against poor people. Nobody cares,” Moore says. "A person can commit a very serious crime and go to the penitentiary and be out in a couple of years.

"We cannot control our streets until we control our penitentiaries and our jails. If they are running amok in the penitentiaries, they’ll run amok on the streets. (American Millstone p. 46)

Another article tells the story of Kevin Tyler, who participated in a gang assault, and then was murdered himself:

Just after 6 p.m. on July 24, 1984, Kevin Tyler left his mother’s 7th-floor apartment at 4555 S. Federal St. in the Robert Taylor Homes public housing project, went outside and started walking north.

He was on his way to another Chicago Housing Authority apartment at 4dI0 S. State St., where he lived with his girlfriend, their two infants and her two other children.

Tyler had lived in the Robert Taylor Homes since infancy. Nearly everyone in his mother’s building knew him. They had watched him grow into an aimless young adult without a job. Day after day, he could be seen loitering with other young men at the building’s entrance or sitting on the benches nearby

Tyler, thin and relatively short, was a product of life in the urban underclass. He had been a gang member since grade school, had dropped out of high school when he was a freshman and had recently signed up for general assistance but had not received any payments.

On the night of Dec. D,1981, at a rhythm-and-blues concert at the International Amphitheatre, an l8 year-old Cicero woman was stripped, beaten, robbed and sexually assaulted by at least seven black youths.

Her two male companions were beaten and robbed, and her girlfriend narrowly escaped the attackers.

“They were just like animals,” the girlfriend said. “I was screaming and kicking, biting and pulling hair, trying to keep them off of me.”

One of the attackers was Tyler.

Tyler had been one of five men who pleaded guilty earlier. Originally charged with attempted rape, deviate sexual assault, robbery, aggravated battery and conspiracy, he entered his guilty plea to a simple charge of aggravated battery and was sentenced to serve 90 days in Cook County Jail and two years’ probation.

(American Millstone p. 48)

Every part of Tyler’s path to crime have been entirely impossible in Salford. Tyler would not have been allowed to live in his mother’s or girlfriend’s government provided housing. Any public assistance would come via the workhouse. Women were under parental authority, and funneled into marrying respectable men. It would have been nigh impossible for a woman to live independently while supporting a loafer.

Another story:

Freddie Hopkins has never been married. The father of her daughters is a 21-year-old who, she believes, has fathered at least eight other children in their North Lawndale neighborhood.

Hopkins met the young man three years ago when he came to visit her younger brother. “He just kept comin’ over,” she recalls. “He would take me where I wanted to go. He had a car. We went to stores, to drive’ins. He was nice. He didn’t give me no hassle.”

Hopkins was taking birth control pills, but she still became pregnant. “Didn’t feel nothin’,” she says.

“Eyerybody else I knew was havin’ babies, so I just went along.”

The young man was elated. "He say: ‘Freddie! You pregnant with my baby boy.’ I say, ‘No, I not.’ I just didn’t -want to believe it. He-put his head to my belly and listened, and he say, ‘Man, I done got me a son."’

…

The young man who thrice made her pregnant never had to worry about marrying her and taking responsibility for his daughters. He knew, from his short lifetime of experience, that the check would be there to support them. (p. 90-92)

…

“Marry? Nothin’ but problems,” says Freddie Hopkins.

“I ain’t ready to settle down. I ain’t going to get married. I got at least 10 more years left of fresh air.”

Marriage, Hopkins explains, has nothing to do with having babies or starting a family. It means you settle down and “don’t have no fun.”

Will she marry the father of her daughters?

“You kidding?” she says. “What I need him for? He bad news.”

It is sometimes said that blaming the poor for not being responsible is victim blaming. But the father in this case is not a victim – he is a winner at the most important life goal: reproducing. He is a prolific victor. In Salford, again, a loafer could have had far less access to these women.

It is also said that it is wrong to blame women for being single moms. The father’s often don’t have steady jobs and are in no way marriage material. The fathers are, as Freddie says, “bad news.” But – what incentive for the father is there to have a job when you get the sex and kids for free? The entire point of the traditional family structure is that the man only gets the good stuff (sex and status) if he puts in the work.

It is said that the rise of single-motherhood is a result of lack of employment opportunities for men. But other societies have had terrible problems of underemployment, while having virtually no problem of single moms. From Tocqueville’s Journeys to Ireland:

Question:. At what number do you estimate those who are une employed in Ireland although they want to work?

A. Two million.

…

The population at the time would have been close to 8 million. So if we accept that number, that means over 50% of the Irish men were unemployed.

But, the problems of unwed mothers was rare:

Q. You have told me that morals were chaste?

A. Yes, extremely chaste. Twenty years of confession have taught me that for a girl to fall is very rare, and for a married woman practically unknown. Public opinion, one might almost say, has gone too far in this direction. A woman suspected is lost for her whole life. I am sure that there are not twenty illegitimate children a year among the Catholic population of Kilkenny which numbers 26,000. Suicide is most rare. Hardly ever in town, still less in the country, does a Catholic fail to make his Easter communion.

Let us return to American Millstone:

The check doesn’t teach people how to budget their money. It doesn’t teach them how to find adequate housing or how to get a good job or a decent education.

It does teach some clear lessons: Don’t work or you’ll lose the check. Don’t marry or you’ll lose the check.

Illinois, unlike many other states, does not make marriage an immediate disqualification for AFDC, though many recipients think it does.

A married woman can receive AFDC in Illinois and 25 other states, but only as long as her husband is unemployed. An unmarried woman can keep her grant if she weds, but only if her new husband is unemployed.

As far as I know, those laws have almost all been changed. But the damage has been done. And there are still often massive financial disincentives to work, or to marry someone who is working.

The “General Assistance” aid that many able body men relied on in 1980s Chicago has also been reduced in some states. But many men go on federal disability pay as an alternative. And then there is the other way for men to get money without working – leaching off of the women of the community:

Benjamin Jones Jt., 22, has been living in North-Lawndale since 1970. Six years ago, he joined a street gang. Four years ago, he was kicked out of Farragut High School for fighting.

For a year, he stayed at home, mostly sleeping and watching television. When he went out, he says, he sweet-talked girls into giving him money from their welfare checks. “You always got to be thinking when you’re talking,” he explains. “Don’t give her time to think.”

Finally, his mother, Lorine, who has worked at Curtiss Candy as a candy wrapper for 20 years, got fed up with him and ordered him to start paying rent.

So Jones went looking for work. He filled out six applications, then stopped.

“You got to have qualifications,” he says. “You have to be a master in this and that. They never call you back’ When they didn’t call, I said, ‘Hey, forget this.’”

So he went on the check. Each month, he receives $154 in general assistance and $79 in food stamps.

Another story reports on “welfare primps”:

But there are also men who take advantage of the situation, men known throughout the inner city as “welfare pimps’”

“They have a woman here, and another there,” says Hattie Williams, a longtime activist in the Oakland neighborhood on the south side. “Two or three women they keep barefoot and pregnant so they can survive with $50 a month or so from each of them.”

’My God,“ says a middle class black woman who works at a west side housing pryject, ”they are all over the place. They know the day the check comes and they wait outside the currency exchange. If a woman doesn’t give them money, she’s beaten."

“One guy here, he got two sisters pregnant. They each have several children by him. And he gets money from both of them.”

To switch books for a moment, Ghettoside, an account of LA ghettos around 2010, describes many underclass males as making money from welfare and side hustles:

Black people in Watts were generally governed by a complex system of etiquette, backed by the threat of violence. This was the shadow that filled the vacuum of legitimate authority. One reason it existed was the neighborhood’s vast underground economy. When your business dealings are illegal, you have no legal recourse. Many poor, “underclass” men of Watts had little to live on except a couple hundred dollars a month in county General Relief. They “cliqued up” for all sorts of illegal enterprises, not just selling drugs and pimping but also fraudulent check schemes, tax cons, unlicensed car repair businesses, or hair braiding. Some bounced from hustle to hustle. They bartered goods, struck deals, and shared proceeds, all off the books. Violence substituted for contract litigation. Young men in Watts frequently compared their participation in so-called gang culture to the way white-collar businesspeople sue customers, competitors, or suppliers in civil courts. They spoke of policing themselves, adjudicating their own disputes. Other people call police when they need help, explained an East Coast Crip gang member. “We pick up the phone and call our homeboys.”

Gangs issued informal “passes”— essentially granting waivers that exempted people from the rules that governed everyone else. A star athlete in a gang neighborhood, for example, might be issued a “pass” that exempted him from participation in gang life. Or passes might be extended to people allowed to conduct illegal businesses in rival territories. “Selling without a pass” was an occasional homicide motive.

Gangs could seem pointlessly self-destructive, but the reason they existed was no mystery. Boys and men always tend to group together for protection. They seek advantage in numbers. Unchecked by a state monopoly on violence, such groupings fight, commit crimes, and ascend to factional dominance as conditions permit. Fundamentally gangs are a consequence of lawlessness, not a cause.

Back to American Millstone, another Chicago Tribune article tells the story of a serial criminal:

[Edward Williams] started stealing cars when he was 12. He and his friends took joy rides through North Side neighborhoods, where “we could always find someone with $100, $150 to stick up,” he remembers.

At 14 he joined a street gang and broke into his first house. At 16, already a heroin addict, he was arrsted four times’ Convicted twice for armed robbery, he served six months in the Cook County Jail.

“If I had never gone to jail, I probably would have ended up getting killed,” Williams says. “We were young and wild on the streets. We thought we were doing what was smart, what was slick.”

Out of jail, Williams went right back to crime. At 17, during a robbery attempt, he shot a man with a sawed off shotgun stolen from a preacher’s house. This time he was sent to prison with a six-year sentence.

Released on parole after five years in stateville correctional Center, it wasn’t long before Williams stole more guns and began using LSD regularly. (p. 66)

…Williams and an 11-year-old boy were stealing tires from the lot of an auto supply store. The youngster was tossing the tires over a fence when a worker ran out of the store and grabbed him.

“He catches him and tucks him under his arm like a sack of potatoes,” Williams recalls. “In my mind I was thinking, ‘I hate all white people.’ I turned around and blew the man away.”

For this he went to prison for nine years. Compare to England of old, where in 1874 a murder as part of an attempted robbery made national news, and the assaultants, two of them of age 17, were hung. Another famous assault and murder in 1884 Blackstone Street murder also led to life imprisonment and hanging for two of the attackers. These types of predatory murders remained extremely rare in England.

After his release:

He found a job as a price reporter for the Chicago Board options Exchange but decided he would rather be a welder and enrolled in a vocational training program. Gilbert helped him find a job as an apprentice welder in Arlington Heights, but he was fired after a week for not showing up. Williams says his car broke down but concedes that he never called the company to explain why he would be absent.

He quit a job as a groundskeeper at the Glenview Naval Air Station after two weeks. “It was hard”, he explains. “I’m not used to doing manual work.”

On a recent visit to the first-floor flat that williams shares with his mother, Gilbert gets more bad news. Williams has quit his latest job with a trucking company.

“I told him he made a stupid move by quitting,” Williams’ mother says. “Now he don’t do nothing but sleep. He acts nervous all the time. Oh, he gets up every day and looks at the paper. I just say you don’t get nothing by looking in the-paper”’

This story illustrates something that I have observed when working with underclass men in trying to get them jobs: many of these men lack the attitudes and habits needed to hold down a job.

And as long as they are able to live off their family or girlfriends, there isn’t much incentive to change those attitudes.

Case workers and activists noticed similar attitudes:

“It’s ridiculous,” says Yvonne Gay, a caseworker with the Illinois Department of Public Aid. “A lot of people are offered a job at minimum wage. And they say, I ain’t working for no minimum wage.’ They haven’t been to school, they have no experience and they say no to a job. I just can’t figure it.”

John Lewis, head of the student Non-violent Coordinating committee in the early 1960s and now a councilman in Atlanta, notes that as a youth he worked as a janitor and “did it with pride and a sense of dignity.”

Yet over the last two decades, he says, something gave people the feeling that it is beneath them, that they’re better than that. People are afraid to get their hands dirty. They think it would belittle their pride to work as a janitor or washing dishes in a kitchen.

“To tell a young black that he should push a broom or wash a floor or wash dishes, they talk like that’s heresy!”

…

Denise williams, a social worker at Tubman Alternative School. “I’ve had several tell me, ‘I want to be a lawyer.’ They’re getting Ds in school. They have no conception of what it takes.” (p. 225)

…

To spend your whole life on welfare is very degrading, but I find this younger generation is proud about it," says Earlean Lindsey, president of the Westside Association of Community Action.

"I mean, the younger generation doesn’t feel the embarrassment that an older person who has been in the workforce before feels when they have to go on welfare. A younger person who has never known any other way feels that’s the way it is.’’

…

’The situation is getting worse,“ Gilbert says [ a case worker]. ”A lot of men on my caseload are very, very young. They don’t have any skills, they’re hard to train, and they’re committing crimes at a younger age."

The average age of ex-offenders contacting the Safer Foundation also is dropping, officials there say, from 25 a decade ago to 21 today.

Gilbert believes that underclass ex-convicts need “intensive deprogramming” if they are to move away from the self-destructive lifestyles they have been raised in. Parole officers try to change basic attitudes, but their individual efforts are no match for the negative influences that permeate poor black communities, he says.

Now it should be noted that these anectdotes are selected examples. There are many counter examples, many people who are working much harder than your typical middle class professional. But the people with these anti-work attitudes are the people who are the problem, and these people exist in a much, much higher proportion than existed in Salford, England. Thus figuring out how to change these attitudes is critical to making these neighborhoods safe and wholesome.

Investing in Education?

It is often said that investing in education is crucial to fixing the cycle of violence. The obvious rejoinder is that mass education is a relatively recent phenomena, yet it is not as if before the advent of mass education we had enormous crime problems in all our towns and cities. And today, even the most deprived ghettos have more years of schooling, and more money spent on schooling, than the elites had a century ago.

Back in 1910s Salford, students had far bigger classes, far more terrible conditions, and far fewer years of schooling. Yet the crime in that community was much lower, and the behavior in school better. Here is Roberts in The Classic Slum describing his school:

…. Under appalling conditions in our school the staff worked earnestly but with no great hope. The building itself stood face on to one of the largest marshaling yards in the North. All day long the roar of a work-a-day world invaded the school hall, where each instructor, shouting in competition, taught up to sixty children massed together. From the log book it is clear that rarely did a week pass with all teachers present. ‘Miss F.’ or ‘Mr D. absent today – ulcerated throat’ appears throughout with monotonous regularity.

One inspector early in the century had complained that “Classrooms are insufficient [four for 450 pupils] and one is without desks. Yet writing is taught in it, thus inducing awkward attitudes and careless work.” Error, though, was easily emendable; scholars wrote on slates and made erasures with saliva and cuff. In a school near by, however, this method was frowned on. There the pupil wishing to ‘rub out’ had to raise a hand and a monitor swung to him a damp sponge fastened to the end of a rod. Another inspector deplored the fact that all our ‘offices’ were without doors, ‘even those under the classroom’. …Time and again others condemned the wretched lighting (open gas jets) and the stench of classrooms.

And yet despite the terrible conditions, the the children were studious and well behaved:

At first the inspectors, conscious of the conditions under which teachers worked, refrained from attacking the staff. ‘The children are well-behaved’, wrote one, ‘and under industrious if not very intelligent instruction.’ ‘Scholars are orderly’, wrote another, ‘and attentive to their work, which is practised under careful conditions.’ ‘Pupils work willingly’, added a third, ‘under teaching of creditable regularity and endeavour.’

The attitudes back then were actually often anti-education, they viewed book learning as subverting work ethic:

Certainly many elders of the time, perhaps the majority, would have agreed wholeheartedly with the factory inspector who said, after the introduction of compulsory education: ‘to keep young persons The percentage of literate inmates of prisons in England and Wales between 1835 and 1900 from work till they are 12 years of age will, I fear, create an objection to labour, which through life they may never be able to overcome’.

…

Very many among the middle-aged and elderly, continuing a veto of their own parents, forbade all books and periodicals on the grounds that they kept women and children from their proper tasks and developed lazy habits. As far as children were concerned, our local council seems to have concurred in this: from the opening of public libraries half a century earlier until 1906, no one under fourteen years of age was allowed membership.

Roberts’ father wanted him to get out of the house and do real work as soon as possible:

we left [school] in droves at the very first hour the law would allow and sought any job at all in factory, mill and shop. But, strangely, I myself wanted to go on learning, and with a passion that puzzled me; an essay prize or two, won in competition against the town’s schools, had perhaps pricked ambition. ‘Isn’t there some examination you could take?’ asked my mother. I inquired of the headmaster. There were, he said vaguely, ‘technical college bursaries’, but he didn’t put pupils in: one needed things like algebra and geometry to pass – quite difficult stuff. Some homework, then, I suggested. He shook his head; he didn’t give homework. Still, my name could go up. I could sit, of course. The old man raised no objections, merely instructing me to ‘get through!’ I sat an incomprehensible paper and failed. When the results were announced weeks after, without having a possible hope of success, I felt sick with disappointment.

One dinner time I saw Father, half-drunk and frowning, fingering a slip of paper. ‘I see yer passed!’ he shouted down the kitchen.

‘Yes,’ I said boldly, ‘I came top!’

He rose, threatening, from his chair. ‘Get out!’ he roared. ‘Get out and find work!’

I went out and found work. The girl at the Juvenile Labour Bureau was very pleasant about it. She gave me a green card. ‘Fill it in,’ she said, ‘and put what you would like to be at the bottom.’

I completed the form and wrote on the last line ‘Journalist’. They did not require any journalists. A boy was needed, though, to sweep up, brew tea and abrade union nuts in a brass shop. I took that.

We have many, many examples of worse schooling yet better neighborhoods and better behavior. Here for instance, is an example I came across in a memoir I was reading about West Philadelphia in the 1960s and 1970s:

So many kids lived in our neighborhood that Most Blessed Sacrament (MBS) was one of the most crowded elementary schools in the country. When I started school at MBS in 1964, there were 101 kids in my first-grade classroom. There were 10 rows of 10 kids. The extra kid sat at a desk in a corner in the front of the classroom. To keep 101 kids under control, the rather large Catholic nun who was my first-grade teacher would walk up and down one row after another, tapping a wooden yardstick against her empty hand. We were all afraid of her, and we all knew she was eventually coming our way.

My classroom was not the only first-grade classroom with at least 100 kids. There were five more classrooms of first graders every bit as crowded as mine.

…

I remember seeing a nun beat the hell out of a kid who was involved in one of the fights with the kids from Mitchell. The beating happened in the coatroom. I was carrying boxes of supplies for my teacher, so I was allowed to use the elevator, which was all the way in the back of the huge coatroom, an open area big enough to hang the coats of hundreds of seventh-graders. I tried to pretend I wasn’t watching, but I saw the whole thing. The nun pushed some coats aside to make room on the metal pole that we hung our coats on. Then she forced the kid to hold on to the metal pole as she whacked him across the back of the legs about six or seven times with a three-sided wooden yardstick. Man, did that look painful. It even sounded painful hearing the kid yell each time he got hit. It just wasn’t right.

Yet, few kids, if any, would go home and tell their parents that a nun beat the hell out of them. Most parents, including my parents, were of the mind that if we did something bad enough for a nun to beat us up, we deserved to get beat up again when we got home. Luckily, only a few of the nuns were that violent. Most of the nuns were nice people who really cared about the kids. But the few crazy nuns seemed to get way too much pleasure out of beating the hell out of young kids. It wasn’t unusual to see those nuns slapping kids across the face, both boys and girls, for small stuff like chewing gum or not paying attention during class. And it wasn’t a gentle slap. It was a hard slap, the kind that left finger marks on the side of the kid’s face. Those were the nuns we all tried to steer clear of.

During the time that this school was overcrowded, the neighborhood was very safe:

…this was the greatest neighborhood a kid my age could grow up in. Like any neighborhood, ours had its share of kids who liked to start trouble. But I can’t imagine any neighborhood being more fun and safe to grow up in. Back then, on a warm June afternoon like today, I didn’t have a care in the world.

I always felt so safe on Cecil Street. On warm summer nights, lots of adults would sit on soft cushions on the top step of the four concrete steps that led from the edge of our front porches down to the sidewalk. Neighbors would sit out for hours, talking with other neighbors, many of them enjoying a cold beer or some other cold drink. I knew everybody on Cecil Street, and they all knew me. In fact, I knew almost everybody in our section of the neighborhood. And I felt safe no matter where I went. All us kids knew that most parents around here looked out for all the kids, not just their own.

Now compare this to recent times. Whenever the issues of schools come up on the Philadelphia subreddit, teachers report problems of bad behavior:

I work in philly. Our bathrooms are nasty. Our heat is fucked up. I have mice in my classroom and holes in the floor. I have more pencils stuck in my ceiling than I have in students’ hands. Today, in another class, students literally threw a desk out an open window. I have supportive parents who tell the kids they’ll whoop them if they misbehave, then those same students exhibit that behavior in the class. source

…

10 years? A friend of mine was a teacher in philly ~15 years ago. She was verbally abused by students on a daily basis, and she left for a private school in the suburbs after a year. Of course, I’m sure it’s been going on longer than that. edit: and the private school paid her less. It wasn’t about the money, she left because of the terrible environment and the fact that the administration was not willing to do anything to help out.

…

Nearly everyone i know that was a philly teacher was forced out by violence and uncaring administrators.

…

Had an ex a few years ago who did not make it through her first year at a north philly public school. She was removed by the administration. She broke up a fight in the hall one day, and the kid who started the fight came bursting into her classroom during one of her classes and went off about shooting her after school for snitching, getting in the way… or some similar hoodrat bullshit. She was forced to leave her job for her own safety. source

…

Schools are hell. A friend of mine works for City Year, and she says that the school she works at is run like a dictatorship. She feels ok about it, because she would actually prefer a system where the kids get in trouble for actual things, rather than arbitrary, punitive chaos. The adults there are just as scared as the children, and my friend had the thousand yard stare of someone who had really seen some shit. tldr- Philadelphia schools are hell. Don’t ask questions you don’t want the answers to. source

At Bartram High in Philadelphia:

A brawl erupted in the school cafeteria this week, with teenagers punching and stomping on one another and on school police. Students set off firecrackers inside the building. And the student who last month knocked a staffer unconscious was back in the halls of the Southwest Philadelphia school.

Staffers were shocked when they saw that the 17-year-old who assaulted Stephenson was back in the school this week, some said. The youth has been charged as a juvenile with aggravated assault, simple assault, and related offenses.

“He was cutting class, roaming the hallways,” said a teacher, who asked not to be identified for fear of retribution. “He spent two days in the building this week, and it seems the administration was not aware.”

On Tuesday, “firecrackers were lit off in the building, on two separate floors,” Calimag said.

The problems of bad behavior do not just remain in the school. In Philadelphia in the past year there have been at least three examples of gangs of forty to fifty kids roaming the streets, attacking innocent people for fun, and injuring them badly enough to hospitalize them. (see here, here, here).

Here is a former Teach For America teacher describing the problems of the modern ghetto school:

A large number of this country’s schools are failing its students—but not in the way that many columnists, education reformers, or school experts would have you believe.

From 2008 to 2010, I taught at the middle school level in Kansas City as a Teach For America corps member. But don’t worry, I’m not going rehash Freedom Writers, and I certainly won’t tell one of those sappy “this is why I Teach For America” stories.

Instead, I want to offer some very candid thoughts about why I think my district and school were such abysmal failures.

When people ask me what I believe was the number one barrier to student achievement at my school, I always offer the same answer: the failure of the school and district to address chronically disruptive students. It was a problem created by negligent leaders who willingly allowed a free-for-all environment that was conducive to chaos instead of learning.

Everything was great for the first three weeks, but then a few students began testing the limits of what was acceptable behavior. It’s one thing when a student throws a paper ball at his friend, or when someone utters a rude comment. It’s quite another thing when a student tells you that she’ll “crack” your “bitch ass” or demands that you “get the fuck out of [her] face”. Unfortunately, as the students soon discovered, our principal offered no support whatsoever. Nearly ever discipline referral sent to the office was returned with a polite reminder to please contact the students’ parents. Clear and consistent consequences simply did not exist—even though they were mandated by the district’s code of conduct.

Once that realization spread, the school effectively went from quality to chaos overnight. The following is but a sample of what an average day looked and sounded like:

- Students standing in the hall and kicking classroom doors for five to ten minutes at a time

- Students fighting

- Teachers pelted with paper, pencils, erasers, and rocks whenever they turned their heads

- Assignments torn up and thrown on the floor the moment they’re passed out

- Teachers cursed at, threatened, and sometimes even assaulted

- Classroom supplies vandalized or thrown about the room

- Groups of students running the halls and showing up to one or two classes at most

- Constant yelling and shouting from the hallways

- Gang writing written on the walls with permanent markers

- Students talking and yelling so loud in the classroom that nobody could hear the teacher

By “students”, I’m of course referring to the 15-25% that were chronically disruptive. The truth is that the overwhelming majority in each class were great kids who came every day ready to learn. Besides being from an impoverished part of town, they were no different than students at any other school.

This wasn’t just a problem at my school. When I spoke with other teachers throughout the district, they told me that the situation at their school was nearly identical to mine. Some of their stories are just as outrageous.

Furthermore, the “intervention” and social work meant to help at-risk kids, actually breeds the opposite behavior, because modern social work has an allergy to discipline. The kid learns for years that flagrant disobedience to authority produces no serious consequences. Then the kid becomes an adult, and the normal rules of the legal system apply, and he is in for a nasty surprise when he challenges a police officer. A commenter on the blog Education Realist gives a report:

I have seen it over and over again. Due to their behavior a child or teenager needs ‘intervention’, ‘help’, or is ‘at risk’. Teachers at first usually, and then a combination of teachers, social workers, and case managers come up with various ‘treatment’ and ‘goals’ for the child/teenager to strive for in their behavior. If the child or teenager ‘acts out’ the members of one of the institutions staffed exclusively by graduates of an approved social-work or education school, or some form of ‘line-worker’ like a (youth care worker) that has been vetted for ‘professional disposition’ by one of those graduates will ‘confront’ the child or teenager about their behavior. It is these confrontations about behavior that lie at the source of the problem. They happen almost entirely on the child or teenagers terms. By design.