What caused the dramatic rise of crime and blight in American cities from 1950 to 2000?

On Reddit’s most lauded history subreddit (/r/AskHistorians) someone asked “What caused the dramatic rise of violent crimes and urban decay in the mid-to-late 1960s?”

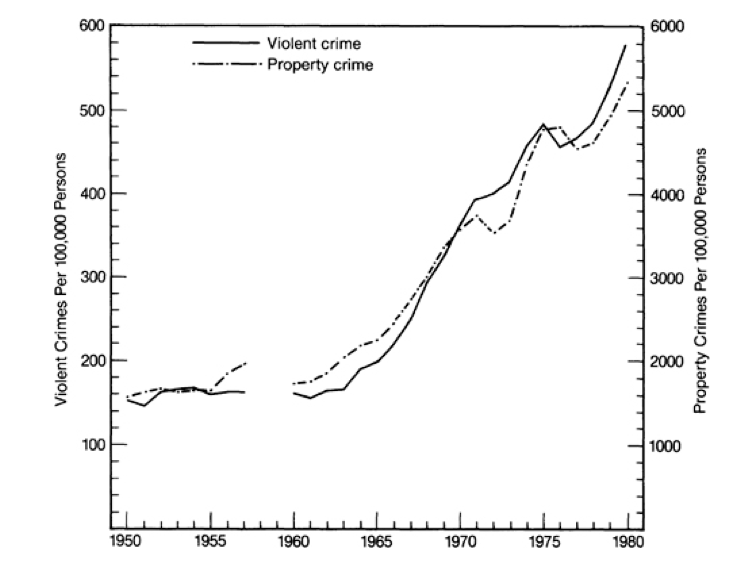

Crime rates in many northern and western American cities skyrocketed during the middle of the 20th century. Here is a table showing the change in homicide rates. Keep in mind, the low homicide rates of the 1910s were before the invention of antibiotics, modern surgery, or wound sterilization techniques!

| City | ~1910 | ~1950 | 1980 | 1991 | 2015 | % increase 1950-1991 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlanta | 29.8 | 35.0 | 47.6 | 59.9 | 20.2 | 68% |

| Baltimore | 5.8 | 9.1 | 27.5 | 40.6 | 55.4 | 346% |

| Boston | 4.6 | 5.3 | 16.3 | 19.7 | 5.7 | 272% |

| Chicago | 9.0 | 7.8 | 28.9 | 32.9 | 28.7 | 322% |

| Cleveland | 6.6 | 10.3 | 46.3 | 34.3 | 16.2 | 233% |

| Detroit | 9.0 | 3.7 | 45.7 | 59.4 | 43.8 | 1,476% |

| Los Angeles | 10.9 | 4.0 | 34.2 | 28.9 | 7.1 | 623% |

| Memphis | 69.7 | 23.6 | 27.3 | 12.8 | ||

| Milwaukee | 3.7 | 2.3 | 11.7 | 25.6 | 24.2 | 1,013% |

| New Orleans | 24.0 | 11.4 | 39.1 | 68.9 | 41.7 | 504% |

| New York City | 5.9 | 3.7 | 25.8 | 29.3 | 3.0 | 692% |

| Newark | 4.0 | 49.4 | 31.8 | 33.3 | ||

| Philadelphia | 4.4 | 5.7 | 25.9 | 27.6 | 17.9 | 384% |

| San Francisco | 13.0 | 5.7 | 16.3 | 12.9 | 6.1 | 128% |

| Seattle | 9.6 | 5.9 | 12.8 | 8.1 | 3.4 | 37% |

| St. Louis | 14.3 | 5.19 | 50.0 | 65.0 | 59.3 | 1,150% |

| Washington DC | 7.8 | 11.8 | 31.5 | 80.6 | 24.1 | 583% |

| Sources |

In addition to rising crime, these cities suffered from an increase in single parent families, joblessness, drug abuse, riots, disorderly schools, and boarded up buildings. You can read narrative descriptions of the situation in books such as American Millstone, Ghettoside, or The Corner. When comparing these modern descriptions of the the ghetto to the muckracking accounts of early 1900s such as How the Other Half Lives or Land of the Dollar, the modern ghettos seem to have much more social dysfunction.

For a video portrayal of the decline, here is Detroit before:

And after:

For a quick narrative account of urban decay, here is an exceprt from an interview of two young Mormon missionaries living in Detroit:

“Nothing surprises us anymore,” Porter [one of the Mormon missionaries] says, smiling. “Back where I’m from, you didn’t get a lot of the things that go on here — gunshots a lot, peeing in public, you see fights, drug deals go down. I remember back home I never saw that. I don’t know; it’s pretty funny.” Moments later, six quick gunshots pop off a block or two away. His face lights up. “There you go!” he says excitedly.

Walking through blown-out neighborhoods has its perils. “The other day we got robbed,” Sturzenegger says. “A guy came up with a gun, actually pointed it to us, but you know it’s funny ’cause we’ve heard other things happen to just regular people around here, they get shot afterwards, but to us that didn’t happen; the guy just took the money, just four bucks, so it was cool.”

“Yeah, we’re poor anyways,” Elder Porter adds, laughing.

They and their fellow elders in Detroit have been attacked by wild dogs, shot at and robbed. They’ve developed a calm fearlessness, earned by time on the streets and emboldened by the conviction that they are being protected from above. During the spring, someone stole their bikes right in front of them. Porter gave chase, found out where the thieves lived from an elderly neighborhood snoop who tipped him off, went to that house and personally took the bikes back. “It was amazing,” he says, grinning.

Our question is thus: what caused this rise in crime and urban decay?

The most upvoted answer on the /r/AskHistorians thread blames deindustrialization, surbanization, and racial segregation:

Deindustrialization and Suburbanization. …As Asia and Europe rebuilt from the war, technology advanced, and America suburbanized, factory jobs moved out of major cities…. As the jobs evaporated, tensions rose. People had left their lives behind in pursuit of jobs which no longer existed, and now they had nothing to do to provide for themselves or their families. They also had nowhere to go. Even blue-collar, affordable suburbs were off-limits due to persistent racism both on the part of real estate developers and neighbors, who would sometimes violently convince African-Americans trying to move in that they weren’t going to stand for it…People with nothing to do and nowhere to go tend to turn to crime. The race riots, crime wave, huge growth of gangs, crack epidemic–I would argue they all had the same root cause, which was the economic desolation of the inner city.

Another commenter adds in:

Don’t forget to mention the practice of blockbusting. Real estate agents would scare whites in urban neighborhoods into thinking that the neighborhood was “becoming black.” Sometimes, they would accomplish this by actually selling a house in the neighborhood to a black family. Sufficiently scared, the white families would sell their houses for below-market prices and move to the suburbs.

The answer given by these two commenters is the answer I was taught when I was in university. My college was in an old American industrial city afflicted with urban decay. Understanding the decline of the city was a keen interest of mine. I took several classes on the subject, did much independent reading, interned at city hall working on economic development, and volunteered in local non-profits.

But since I graduated, I have done more reading and research, and was exposed to viewpoints that were never included in my class reading lists. And as I have read, it became more and more obvious that the standard academic narrative was simply wrong. Statistics, memoirs, and ethnography all contradicted the mainstream view. The problem with blaming the rise on crime as being caused by middle-class people leaving, is that the crime came first. While there was a gradual move of whites from the city to the suburbs starting the 1950s, this flow turned into a flood only after rising violence.

Let us start with the statistics first.

From the 1940s to the 1980s, two trends occurred. The demographics of major northern cities such as Detroit, Baltimore, Philadelphia, St. Louis, etc, went from 5-20% black to 40-80% black. At the same time, homicide rates rose by an order of magnitude – from around 5 per 100,000 to 20-80 per 100,000.

If job loss and deindustrialization caused the homicide spike, we should expect black populations in these cities to have a low homicide rate in the 1940s and 1950s and then a ten-times higher homicide rate in the 1980s, after the job loss.

But that is not the case – the homicide rates in black populations were high all along. At least half of the 1,000% increase in crime can be explained purely by the statistics of composition. If you have group A that commits crime at 35 per 100,000, and group B that commits crime at 2 per 100,000, and if your population goes from 10% to 60% A, then homicide rates will go from ~5 to ~20.

The problem of high homicide rates among black Americans did not start only after they moved to the city and white people left the city. The problem goes back all the way to the years after the Civil War. Nor are the high crime-rates among black people in the south a myth of neo-Confederate historians – it is documented and undisputed by many liberal and African-American historians.

Nicholas Lemann wrote in his award winning book The Promised Land:

It is clear that whatever the cause of its differentness, black sharecropper society on the eve of the introduction of the mechanical cotton picker was the equivalent of big-city ghetto society today in many ways. It was the national center of illegitimate childbearing and of the female-headed family. It had the worst public education system in the country, the one whose students were most likely to leave school before finishing and most likely to be illiterate even if they did finish. It had an extemely high rate of violent crime: in 1933, the six states with the highest murder rates were all in the South, and most of the murders were black-on-black. Sexually transmitted disease and substance abuse were nationally known as special problems of the black rural South; home-brew whiskey was much more physically perilous than crack cocaine is today, if less addictive, and David Cohn reported that blacks were using cocaine in the towns of the Delta before World War II.

In the 1910s, Raymond Fosdick, a Princeton graduate and city investigator, was hired by John Rockefeller Jr to study both European and American police systems. He wrote a report Crime in America and the Police which is very much worth reading today. In every city where he looked up the statistics – Chicago, Washington DC, Memphis, St. Louis – the rate of felony homicide arrests for blacks was 5 to 20 times greater for blacks than for whites.

In 1904, WEB Du Bois sat as secretary at conference in Atlanta about crime in Georgia. The conference resolved:

The Ninth Atlanta Conference, after a study of crime among Negroes in Georgia, has come to these conclusions: 1. The amount of crime among Negroes in this state is very great. This is a dangerous and threatening phenomenon. It means that large numbers of the freedmen’s sons have not yet learned to be law-abiding citizens and steady workers, and until they do so the progress of the race, of the South, and of the nation will be retarded….

One of the conference goers made a statement:

That crime and vagrancy should follow emancipation was inevitable. A nation cannot systematically degrade labor without in some degree debauching the laborer. But there can be no doubt that the indiscriminate method by which Southern courts dealt with the freedmen after the war increased crime and vagabondage to an enormous extent. There are no reliable statistics to which one can safely appeal to measure exactly the growth of crime among the emancipated slaves. About seventy percent of all prisoners in the South are black; this, however, is in part explained by the fact that accused Negroes are still easily convicted and get long sentences, while whites still continue to escape the penalty of many crimes even among themselves. And yet, allowing for all this there can be no reasonable doubt but that there has arisen in the South since the war a class of black criminals, loafers and ne’er-do-wells who are a menace to their fellows, both black and white.

Another Southern writer described his own perceptions, also in 1904:

Twenty five years ago women went unaccompanied and unafraid throughout the South as they still go throughout the North. Today no white woman or girl or female child goes alone out of sight of the house except on necessity, and no man leaves his wife alone in his house if he can help it. Cases have occurred of assault and murder in broad day within sight and sound of the victim’s home.

W.E.B. Du Bois himself acknowledged the problem of crime in his 1899 book The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study:

In the city of Philadelphia the increasing number of bold and daring crimes committed by Negroes in the last ten years has focused the attention of the city on this subject. There is a widespread feeling that something is wrong with a race that is responsible for so much crime, and that strong remedies are called for. One has but to visit the corridors of the public buildings, when the courts are in session, to realize the part played in law-breaking by the Negro population. The various slum centres of the colored criminal population have lately been the objects of much philanthropic effort, and the work there has aroused discussion. Judges on the bench have discussed the matter. Indeed, to the minds of many, this is the real Negro problem…

That it is a vast problem a glance at statistics will show; and since 1880 it has been steadily growing….It seems plain in the first place that the 4 percent of the population of Philadelphia having Negro blood furnished from 1885 to 1889, 14 per cent of the serious crimes, and from 1890 to 1895, 22.5 percent….It has been charged by some Negroes that color prejudice plays some part, but there is no tangible proof of this, save perhaps that there is apt to be a certain presumption of guilt when a Negro is accused, on the part of police, public and judge. All these considerations somewhat modify our judgment of the moral status of the mass of Negroes. And yet, with all allowances, there remains a vast problem of crime.

In the Philadelphia of 1950, before white flight and employer flight, the black homicide rate was around 23 per 100,000 while for whites it was around 2 per 100,000.

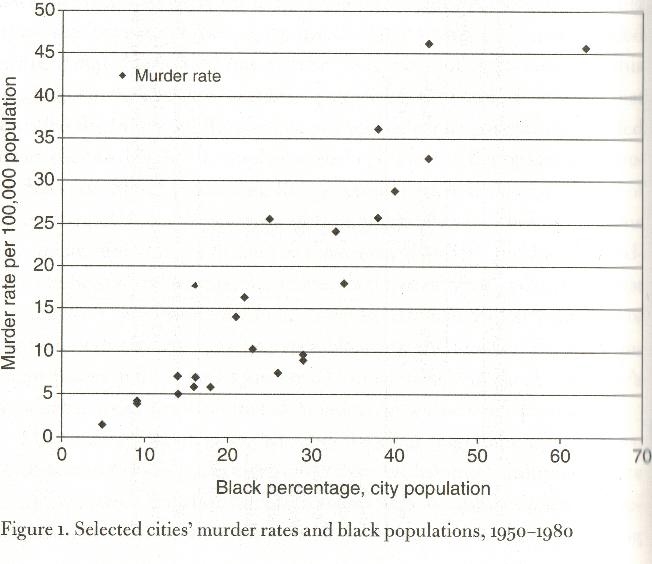

Overall, here is a plot of the homicide rate versus the percentage black population of the city, using cities across the country, sampled at many points of time over the 20th century (from William Stuntz’s The Collapse of American Criminal Justice):

So what actually happened to transform these cities?

In the middle of the 20th century there was the Great Migration of blacks from the south to take advantage of manufacturing jobs. As manufacturing employment saturated, the northern cities continued to attract migrants by offering very generous welfare payments. Black people often moved north and then soon went on public assistance, and were converted into a voting block for the local politicians. Lait and Mortimer wrote in their 1950 book Chicago Confidential (their ‘Confidential’ series of books were sort of 1950s equivalent of the today’s Vice Travel guides. The books are more salacious, but often more honest and accurate, than the more mainstream press):

One of the greatest mass movements of humanity in the history of our country took place during the last war, when some 2,000,000 rural Negroes left the South to glean the swollen wages of the war plants in the industrial North. Chicago was the nearest Golconda, easiest to reach. It got the biggest share in the scramble. How many is not known and may never be known.

That many of these were proselyted, much like the Puerto Ricans were induced to flock to Manhatttan is definite. Democrats below the Mason and Dixon Line were a dime a dozen. Chicago often went Republican and Illinois generally did. The New Deal needed Illinois. It turned the tide in Chicago with new Negro votes and in time Chicago turned the state, took it away from the G.O.P..

…

Into mansions and terrace apartment buildings, on boulevards, parkways, and leafy avenues, flooded the thousands whose backs were weary of picking cotton and herding hogs, of being an inferior people often by law as well as social and financial opportunity. Bronzeville became a Negro heaven. Nowhere in the nation were Negroes so well off, so well treated and so well housed.

…

During the war, when the Chicago labor shortage was more severe than in most places because of the diversity of her plants and her unequaled transportation setup, it was not unique for a farmhand who had never owned $10 at one time to earn $200 a week with overtime. This started the Bronzeville boom, with its drinking and doping and the resultant laxities that blossomed into flagrant vice.

Most of these people had left behind them the influences which they had come to respect, in entirely different conditions. The problems attending migration from rural areas proved particularly acute with the youth. To get the swollen ages, the parents left their children largely to themselves, and they went wild. When the layoffs came, the children had been up North long enough to refuse the conditions of ordinary living, such as most Negroes in this country are accustomed to. Vice and crime were easy money. Politicians had discovered that they could remain in office indefinitely by buying the votes of entire large segments of the population. Newly arrived Negroes, not allowed to vote where they were born and raised, were easily organized by astute professionals, black and white, and bribed, with money and immunity, to ballot in blocs. They were encouraged to send for more of their people and special cheap rates were procured to bring them on. As the voters began to realize what was being done with them, they held out somewhat and new consideration was flaunted to them: jobs. Government, state, county, city jobs, and when these began to run out, private jobs. Whereas in New York the social do-gooders and the radical newspapers have fought long and with little effect to open the doors for other than menial work to Negroes, in Chicago the politicians themselves took up the causes, and they didn’t plead, they demanded.

Employers need licenses, signs, porticos, immunity for petty violations, and what not, for which they must get their alderman’s say so. They can be ruined with high assessments (in Illinois there is a personal property as well as real estate and business tax, which is juggled and is brought very close to individuals)….Word was brought impressively to employers in wholesale, retail, public utility, and other institutions of trade that they had better take on Negroes, and not only as porters and elevator operators. This was exercised not only by the Negro politicians. They had become a major factor in the election of higher white candidates. These orders came from up above.

The economic need for more Negroes in Chicago had passed. The stockyards, common labor, house servants, and restaurant workers were in competitive fields. But there was a desparate political need. As more Negroes were colonized from the South, more were placed on relief immediately – often illegally – and the trickle of employment by persuasive blackmail never stopped. The Negroes began to enter the underworld life, not in a spirit of mischief and high binges but for direct financial results.

…

Many of the liquor joints are owned by white outsiders who pay Negro managers to front and represent themselves as owners. In that way, when a license is revoked, the ostensible Negro owner can have it restored where a white man wouldn’t have a chance. This sets up again the phenomenon of the Negro in the political position of the “master race.”

There are many instances, not surreptitious, which can prove this. Chicago’s tax ordinances, like New York’s, forbid more than one party riding in a cab. This is enforced except as to cabs owned by Negroes and driven by Negroes, who many carry as many riders as they wish and pick them up when their cabs are not filled. Many act as jitneys, cruising boulevards and taking fares at 15 cents, also forbidden by law. Cops have learned not to bother Negro cab drivers on these or other traffic violations. They don’t want to tangle with Dawson.

At the same time government efforts worked to break down segregation and move blacks into white neighborhoods and schools. This may sound contradictory to the standard history, in which we learn that red-lining and housing project selection was used to keep blacks out of the white suburbs. But there is no contradiction. Both happened. Before World War II, virtually all neighborhoods were segregated by ethnicity. Whether it be due to laws, convenants, informal violence, or personal cultural affinity – in most cities blacks, Irish, Poles, Jews, Italians, all lived in their own neighorhoods, rarely stepping foot in the turf of another ethnicity. After World War II, blacks were integrated into white neighborhoods in the city, and kept out of white neighborhoods in the suburbs.

As Michael Jones notes in his book Slaughter of the Cities, much is written about the FHA and red-lining, while the USHA efforts to integrate are forgotten:

The FHA was every bit as much a part of the federal government as the USHA, but they pursued diametrically opposed policies when it came to race. Whereas the USHA was adamant in pursuing an aggressive policy of integration in every project it funded in every city where they got built, the FHA pursued an equally aggressive policy of racial segregation, refusing to guarantee loans in areas where there was even a threat of racial mixing, no matter how high the quality of the housing stock.

By the early 1970s the FHA changed policy and lavished loans on black people moving into white neighborhoods in Chicago and other American cities:

“In 1972, in Chicago and in every other city in the nation, almost anyone could get a home mortgage, including borrowers who didn’t earn enough to pay them off, on just about any house, for any reason. … And just like the recent adventure in lending beyond any rational limits, the mortgage disaster of the early 1970s was born from a lofty ideological conviction that enabled the basest of crimes and most foolish of gambles under its cover, insulated from almost any scrutiny until the damage was already done.” …Across the country, neighborhood destruction became a booming business, financed by the federal government. In Chicago they called it ‘panic peddling.’ In New York, it was ‘blockbusting.’ … The FHA-insured loans threw gasoline on that smoldering fire. … Indeed, the insurance made it profitable to seek out the most impoverished and unreliable borrowers, since the sooner a borrower defaulted on a loan, the more quickly the lender would get paid back in full by FHA. (Our Lot , Katz)

Other integration efforts included: the 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer case banning the enforcement of racial covenents; 1954 Brown decision banning school segregation; the Green v. New Kent decision requiring cities to take affirmative measures to racially balance schools; the many local court orders forcing school busing; the 1968 Fair Housing act; and the various acts in the 1970s that tried to ban formal and informal red-lining.

There were also many local efforts to move blacks into white neighborhoods. Chicago’s infamous Cabrini Green project was built in an Italian neighborhood. As Michael Jones notes: “The Defender [a black newspaper] hailed the rapid integration of the area and proclaimed, over optimistically that Little Hell was become a ‘seventh Heaven’ for blacks.” The Philadelphia Housing Authority built the Raymond Rosen Homes and Schuylkill Falls as mixed-race housing projects, one in a black neighborhood, one in a white neighborhood. In Boston, the B-Burg lending program gave subsidized mortgages to black families from Roxbury to move into Jewish/white Dorchester.

It is not entirely clear what the motives were of the political leaders pushing these projects. Certainly, some earnestly believed in the idea of integration being good for all. But Michael Jones argues in his Slaughter of the Cities that the WASP elite at the time had more cynical reasons. In his account the elite feared the political, social, and demographic power of the ethnic, Catholic Poles and Irish. The W.A.S.P.’s elite wanted to obliterate the ethnic white tribal identity by breaking up their neighborhoods.

When the black population moved into white areas, whites noticed a stark rise in crime and disorder. In response, numerous whites would fight back and shout slurs. This lead to a hardening of feelings on both sides. At the same time, both white leftist elites and black leaders started pushing black power. This era saw the rise of Malcolm X preaching about “white devils.” It saw the rise of the Black Panthers, Nation of Islam, the Black Liberation Army, the Family, and the Symbionese Liberation Army.

One white civil rights activist recounts going to racial justice meetings in 1967:

In those terrible days of open conflict, I was being taken into the inner cities, usually by black militants, as an observer. I hardly ever opened my mouth. The day was past when black people wanted any advice from white men. I was taken in simply to view it from the inside, so that in the event we did come to open genocidal conflict, there would be someone to give another view of history. And another view I got. I attended enraged meetings where black men, women, children, students discussed their experiences. Everyone was saying the turmoil was the work of young blacks. That was not true. Middle-aged and elderly black people attended those meetings everywhere, and burned with rage. In Wichita, Kansas, I heard a young college student say the kinds of things that were being said in all the cities. He recounted an injustice done him in that community. He showed wounds where he had been beaten by white men.

“We’ve tried everything decent,” he said loudly.

“Yes,” the audience responded. “Yes. Who can doubt that?”

“We asked for justice and they fed us committees,” he shouted.

“Yes.”

“They’ve even got committees to decide how much self- determination we’re going to have.”

“Take ten!” someone shouted from the back of the room.

“Take ten!” a few responded.

After he had spoken, the young man came over to my chair, almost sobbing with frustration. He looked into my eyes with eyes that were wild with anguish and whispered while we shook hands, “When you go back, will you do me a favor?”

“Yes, if I can,” I said. “When you go back out there, will you tell your friend, Jesus Christ, and your friend, Martin Luther King - ‘shit!’” He spat out the word with the deepest despair I have ever heard in a human voice.

On the streets, young black men would call out, “Take ten!” to one another. Whites thought they were talking about a ten- minute coffee break. What they were really saying was that this country was moving toward the destruction of black people, and since the proportion was ten whites to every black, then black men should take ten white lives for every black life taken by white men. ( John Howard Griffin, Black Like Me)

In this atmosphere, some young black men started deliberately preying upon the white folks who lived near by. Those whites who could afford to, fled to the suburbs to escape the violence. As the numbers turned, the remaining whites were outnumbered, and they too eventually fled, often at great financial loss.

The above story is repeated over-and-over again, in memoirs and ethnographies.

Jonathan Reider, a Yale educated liberal sociology professor, did an ethnography of Canarsie, Brooklyn to try and understand why the working class residents had started voting Republican. He found that the residents were terrified of (black) crime:

Canarsie suffered a rise in burglaries and muggings in the late 1970s, but most local police considered the neighborhood relatively safe. However, the residents could not sequester themselves away from the rest of the metropolis. They lived next door to some of the highest crime areas in the entire city. To work, to visit, and to shop, they had to travel back and forth through the city, and their mobility made them vulnerable to attack.

I met few residents who were strangers to street crime. If they had not been victimized, usually only one link in the chain of intimacy separated them from the victims-kin, neighbors, and friends. Canarsians spoke about crime with more unanimity than they achieved on any other subject, and they spoke often and forcefully. Most had a favorite story of horror. A trucker remembered defecating in his pants a few years earlier when five black youths cornered him in an elevator and placed a knifeblade against his throat. “They got two hundred dollars and a gold watch. They told me, `Listen you white motherfucker, you ain’t calling the law.’ I ran and got in my car and set off the alarm. A group of blacks got around the car. If anybody made a move, I’d have run them over. The police came and we caught one of them. The judge gave them a fucking two-year probation.” The experience left an indelible imprint. He still relived the humiliation of soiling himself.

…

In Canarsie High School, violence between the races had broken the peace recurrently since the school was completed in the 1960s. By 1977 the student population was 27 percent black. The school was not a wildly dangerous place, nor did antagonism prevent friendships from forming across the barrier of race, and students were not all equally likely to become embroiled in disputes. Yet the mixing of adolescent boys from different economic and racial backgrounds grounds created a tinderbox in which a simple dispute could turn into full-fledged racial war. In the absence of agreement on territorial rights, hostile factions vied for primacy in hallways, classrooms, stairwells, bathrooms, the lunchroom, playgrounds, and exits. Italian boys often inveighed against the incursion of blacks, and their gait and mien….

Nodding off in a drug-induced haze, one youth slurred:

The blacks are trying to take over Canarsie High School. The teachers are afraid of them. That’s why the whites get blamed for every little thing. I seen Roots, man, you know, I say it’s not really our fault in a way, ’cause it was really the English who tortured them. The nig*ers hint it to you, like you’re responsible. In history class we talked about it. They just look at you and start talking about Roots, “these honkies this” and “these honkies that.” They shouldn’t have put the blacks in slavery then. They should do it now! Keep ’em in hand!

…

After a flurry of muggings by black youths around the subway station near the low-income project, the residents were especially unnerved…One evening dozens of people crowded into a synagogue basement to discuss the muggins. The rabbi sermonized, "…Five blacks broke the ribs and shoulder bone of the last person who was attacked. The entire perimeter of the proejct has become hazardous….

…

Many Canarsian’s, concluding that vast stretches of Brooklyn had become dangerous places, nervously shifted their patterns of movement through the city or retreated into protective asylums…Whites ceded many areas of the city, but crime followed them into Canarsie. Social policy and administrative decisions, such as housing for the poor in middle income neighborhoods, school zoning and busing schemes, and inadaquate screening of public housing, increased the permeability of the community."

…

One police officer explained that he earned his living by getting mugged. On his roving beat he had been mugged hundreds of times in five years. “I only been mugged by a white buy one time. All right, one instance, I went to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. They got a huge mugging rate there. I was dressed like an old man, a scar on my face, a little blood dripping like I was just anaccident, a cast on my arm, wearing old clothes.” He had been out on the street for barely five or ten minutes when a band of black youths approached him. “First words I heard were, ‘Get the old white man.’ Somebody got around me, I got kicked, I got punched, one guy says, ‘Grab him, let’s take his wallet,’ I got stabbed in the hand. It was a savage thing. I also found that it was because I was white. ‘Look at the old white guy’, ‘Let’s get the old white guy,’ ‘Get the fucking white scumbag.’ What the hell does ‘white’ mean?”

Moving on to Baltimore, one man who grew up there during the 1960’s describes his own experience of “white flight”:

An urban myth tries to explain what happened when the black families moved into those newly emptied houses. The following description also from BlackPast.org describes the currently accepted “truth”:

[The inflated cost of the suddenly available houses] placed an onerous burden on black homeowners. Already facing steep housing payments, they often found it difficult to get bank loans to make needed repairs on their new homes. Renters in these integrated enclaves faced similar difficulties, notably substandard living conditions imposed by slumlords who viewed these properties as expendable commodities ripe for exploitation. These problems exacerbated declining housing prices and equity loss.

That is exactly what everyone believes is an irrefutable truth, but I witnessed something different. Before the riots, my grandmother’s well-maintained neighborhood was a neighborhood of rose gardens and neighbors talking over the back fence, of bakeries and a walk to the local church on Sundays, of kids playing baseball in the side streets and the local family dog getting scraps from everyone up and down the block.

In less than a year, it no longer looked familiar. There were boarded-up windows and scary guys hanging on corners, trash in the alleys and chained dogs surrounded by piles of excrement in backyards, loud porch parties and screeching children fighting on the front street.

My parents watched a young teen take a baseball bat to the uprights on the railing of the front porch across the street, a bat he used to systematically smash each upright until the porch looked like a mouth of broken and twisted teeth. This was not slumlord neglect, but purposeful destruction of a recently beautiful neighborhood.

Then the bullets came through my grandparents’ front bedroom window one night, hitting the wall just above their bed. Fear made my grandparents flee, too. The agent who bought the house for far less than it was worth advised my father to take the newel post statuette and the stained glass over the front door and windows, because they would be destroyed shortly after the house was occupied. Destruction of those beautiful Art Deco architectural elements is exactly what happened not much later.

…

Students from poor black schools were bused to white, middle-class schools miles away from their neighborhoods, homes, and experiences. White middle-class students were bused to poor black schools also miles away from their neighborhoods, homes, and experiences.

This was supposed to equalize everything, but you cannot force people from either neighborhood to change overnight. The clashes were inevitable. Tough kids from poor neighborhoods used to the life on the streets bullied and beat up the middle-class kids who had no idea how to respond, at least at the junior high level.

After months of my brothers and sister getting attacked, the final straw for my parents came one day when my little brother, a sweet, rather sickly little boy, was playing in the alley where we all played. He was riding his Big Wheel up and down behind the house. My mother periodically checked on him from the kitchen window. Then he didn’t pass by for a bit, and she went looking for him.

They kept poking him with sticks and shoving his Big Wheel with their foot, saying, ‘What you gonna do, white boy?’

She found him surrounded by several junior-high-age students who had been bused to the neighborhood school but were playing hooky. They would not let him go home. They kept poking him with sticks and shoving his Big Wheel with their foot, saying, “What you gonna do, white boy?” My mother found him choking in tears and now utterly afraid of a neighborhood that until that day had been utterly safe.

In Philadelphia, one man (Kevin Purcell) wrote a memoir of his time growing up, as the neighborhood turned from white to black. There are many comments in the Amazon reviews, saying, “I grew up near by, I had the same experiences.”

Early in the book, Purcell describes his first experience being accosted when traveling through a neighborhood block that was becoming black:

When we walked past the supermarket, I saw a few black people mixed in with all the white people who were shopping. I never used to see black people in this area. But now the area near 54th Street was one of the first parts of our neighborhood where a lot of white families were moving out, and a lot of black families were moving in. Two of my friends from Most Blessed Sacrament School (MBS) who lived in this area moved out last year. Both of their families moved to the suburbs. And both of their houses were bought by black families.

Once in a while, I’d hear about fights breaking out in the 54th Street area between black kids and white kids. But all the stories I heard involved older teenagers. I figured kids our age had nothing to worry about. So as we made our way to Tip O’Leary’s, our only care in the world was hoping we could find John Smith sneaks in our size.

The second we set foot outside Tip O’Leary’s store, we were surrounded by six or seven black kids who were a lot bigger and older than we were. A couple of them looked about 13 or 14 years old.

The biggest kid said, “Hand over your sneaks, all y’all.”

I was stunned. We were actually being robbed. I had no idea what to do. I looked over at my brother Joe, who was definitely a lot crazier than me and Larry. Joe lifted his bag up toward the kids as if he was going to hand his sneaks over. Then he swung the bag toward the faces of two of the black kids and yelled, “Run!”

And run we did. The three of us sprinted down Chester Avenue toward 55th Street. As we were running, I could see there were still lots of people out shopping up ahead. If we can make it to 55th Street, I thought to myself, we’ll be safe. When we got to 55th Street, I looked back. Sure enough, the kids had stopped chasing us.

I decided right then and there I was not going back to the 54th Street area any time soon. When we got home, we told Mom what happened. She wanted to call the cops. We tried to convince her not to. She finally agreed, saying, “Okay, but you’re not going over to 54th Street again without me or Dad.”

The situation gradually escalated. Some white teenagers chased away some black teens who were trying to play at “their” playground. And then the blacks came back a few weeks later to counter-attack:

The next day, the same six black kids came back to Myers playground. They played basketball for about an hour, and then they left. After they left, I could tell some of the older white guys were getting pissed off that these black kids were playing basketball in Myers playground.

“Why the fuck they have to come here?” I overheard one of the older guys say.

Then another one said, “This is our playground. They got their own fucking playground down on 49th Street.”

He was talking about the playground on 49th and Kingsessing Avenue. I was never in that playground. But every time I’d ride by it on the “13” trolley, most of the people hanging out there were black. So I guess he was right, there was a playground for blacks at 49th Street. Still, it would be a long walk from 58th Street all the way to 49th Street just to play some basketball, especially when there were some empty courts during the day right here at Myers playground.

The following day, the same six black kids came back to Myers playground again….All of a sudden, I heard four or five bursts of glass shattering behind me in the basketball courts. I quickly turned around and saw about 10 older white kids chasing after the six black kids. At first, the black kids looked stunned. Then they took off running, jumped over the short fence, and continued out onto Kingsessing Avenue toward 58th Street. They even left their basketball behind.

After the black kids were out of sight, one of the older guys yelled, “This is our playground. We don’t want no fucking nig*ers around here.”

I didn’t like seeing those black kids getting chased away like that. Just three weeks earlier, at Tip O’Leary’s, it was me and my brothers who were outnumbered and being chased. I didn’t like that feeling. And I didn’t like seeing anybody, black or white, have to feel the same way.

I was glad none of the black kids got hurt. But I had a feeling they wouldn’t be coming back. And they didn’t come back the next day, or the next, or the next. Little did I know that, when they would return, they’d return with a vengeance.

…

Our team was playing the late game on the baseball field closest to 59th and Chester Avenue, farthest away from the basketball courts. I forget what inning it was, probably the sixth or seventh because the sky was starting to get dark. Our team was up to bat. I wasn’t scheduled to bat that inning, so I was sitting on the team bench. Suddenly, I heard loud screams coming from the other baseball field, the one closest to the basketball courts. I looked up and saw about 20 black people, both teenagers and adults, swinging belts and broom handles and throwing bottles and rocks at the mostly white people who had been watching the game from the metal bleachers, but were now running for cover.

Within minutes, cop cars with sirens blaring raced into Myers playground through both the Kingsessing Avenue and Chester Avenue entrances. The black guys tried to get away, and most of them did. Two were caught and arrested. Later, when things had settled down, I overheard two older white kids talking:

“Some of those younger nig*ers looked like the kids we chased off the basketball courts last week,” one older white kid said.

“Yeah, I think it was them,” said the other, “they looked real familiar.”

…

Before that fight at Myers playground, there were already a lot of “For Sale” signs on most streets in the area. After the fight, it seemed like there were twice as many. I guess a lot of people decided they’d seen enough. They were moving out.

As soon as I walked through the alley to Alden Street, I couldn’t miss the huge moving van parked outside the Jordon’s house, completely blocking the narrow, When I walked to the Jordon’s house to say goodbye, both parents had a redness around their eyes. It looked like they’d both been crying. The Jordons were the third family in the Cecil Street area who’d moved out in the past couple of months. All three times, I noticed that the parents seemed to be upset about leaving. And their kids were usually even more upset. About a month earlier, I saw two of the McSorley brothers crying on the day they were moving out. They were about eight and nine years old, and they obviously didn’t want to move. No kid in his right mind would want to move out of this neighborhood. Each time I saw a family moving out, I thought to myself, If they’re that upset about moving out, then why are they moving in the first place? After all, things still weren’t too bad in our section of the neighborhood. I was glad we weren’t moving.

As more white families moved out, the situation became much worse for Purcell and other whites who remained:

Our little corner of Myers playground, near 59th and Chester Avenue, was the only part of the playground where we could still hang out. Black kids were now hanging out on the basketball courts and every other part of the playground, even near the Old House. We were more outnumbered than ever before, especially now that more white kids than ever had gone down to the Jersey shore for the summer….And this year, a few of the guys, including my friend Chris, were sent away for the summer to live with relatives. Chris was spending the summer with his cousins down the shore. A lot of parents were trying to find any way possible to get their kids out of this neighborhood that was getting more and more dangerous by the day. Because so few of us were hanging out in our little corner of Myers playground, we would often get attacked by black kids throwing rocks and bottles. We’d fight back for a while. But we were usually so outnumbered we’d have to retreat down Chester Avenue toward 60th Street, which was still a mostly white area. It was easy to see that Myers playground was not going to be a safe place to hang out that summer.

During that summer, there were times I found myself thinking about our situation compared to what I used to think our lives would be like as 12-year-olds. I expected we’d all be playing in summer baseball and basketball leagues at Myers playground every night. I expected we’d all be hanging out in the playground with a big group of guys and girls, flirting with each other and doing other normal stuff most kids our age were doing. I never expected this. I never expected that all the baseball and basketball summer leagues at Myers playground would be cancelled because of all the racial trouble. I never expected that we’d have nowhere to even play basketball anymore. Every time we tried to play on the outside courts at Myers, we’d get attacked. So we didn’t even bother trying. Man, did I miss playing basketball.

A few years later Kevin’s friend Doug was set upon and murdered while walking home from playing basketball:

What made Doug’s death even harder to accept was this: Doug and Tommy never hung out with us on weekends, or were part of our so-called “gang.” Doug worked a lot of hours at the beer distributor. I think Tommy had a job, too. They were just two nice kids who loved to play basketball with the boys in MBS gym. Nobody deserved to die that way. But Doug was probably the least deserving of all.

And I never saw Tommy again after the night Doug was killed. No one did. I heard his family moved him out of the neighborhood the very next day. In fact, after Doug’s death, there were four or five white kids from the neighborhood I never saw again.

My thoughts ranged from seeking revenge to a desire to get the hell out of this neighborhood. My anger grew deeper on the night of Doug’s viewing. His viewing was at a popular funeral home near 53rd and Chester Avenue. Nearly all the families living in that area now were black. Dozens of us lined the sidewalk outside the funeral home as we waited to say our final goodbyes.

All of a sudden, we heard the voices of a group of black kids from a half-block away. They were laughing and yelling at us.

One yelled, “Y’all goin’ to see the dead honky!”

A couple others kept chanting, “Dead honky! Dead honky!”

A bunch of us tried to go after them, but the cops held us back as the black kids scattered.

After Doug’s death, Mom and Dad were more determined than ever to move us out of the neighborhood. But they still couldn’t sell our house. And if they couldn’t sell our house, we couldn’t move. It was that simple. In the seven months our house had been up for sale, no one had come to look at it. Mom was so frustrated. To make matters even worse, Mom told me the realtor gave her some bad news. The realtor told Mom that, even if he found a buyer, our house was now only worth about $3,500. Mom was hoping she could get $6,000, which was still less than the $7,000 Mom and Dad paid for the house back in 1956. right a few years earlier when they kept calling Mom, warning her that if she didn’t sell her house soon, she wouldn’t get much money for it later.

Purcell’s story contradicts the narrative that white people were primarily enticed out of the city by government subdized mortgages. Many of the people did not want to leave and suffered considerable financial losses when they did leave. Nor is blaming the block busting real estate agents sufficient – block busting only worked because the threats were backed by real violence. Blame the block busters, but also blame the people perpertrating and enabling the violence.

Norman Podhoretz grew up in a Jewish family in Brownsville, Brooklyn. His “family was leftist, with his elder sister joining a socialist youth movement.” He later went to Columbia and became a leading neo-conservative thinker. His experiences growing up were central to his rejection of the leftist worldview. He wrote about these experiences in a 1963 essay My Negro Problem and Ours:

Two ideas puzzled me deeply as a child growing up in Brooklyn during the 1930’s in what today would be called an integrated neighborhood. One of them was that all Jews were rich; the other was that all Negroes were persecuted. These ideas had appeared in print; therefore they must be true.

And so for a long time I was puzzled to think that Jews were supposed to be rich when the only Jews I knew were poor, and that Negroes were supposed to be persecuted when it was the Negroes who were doing the only persecuting I knew about—and doing it, moreover, to me. During the early years of the war, when my older sister joined a left-wing youth organization, I remember my astonishment at hearing her passionately denounce my father for thinking that Jews were worse off than Negroes. To me, at the age of twelve, it seemed very clear that Negroes were better off than Jews—indeed, than all whites. A city boy’s world is contained within three or four square blocks, and in my world it was the whites, the Italians and Jews, who feared the Negroes, not the other way around. The Negroes were tougher than we were, more ruthless, and on the whole they were better athletes.

The orphanage across the street is torn down, a city housing project begins to rise in its place, and on the marvelous vacant lot next to the old orphanage they are building a playground. Much excitement and anticipation as Opening Day draws near. Mayor LaGuardia himself comes to dedicate this great gesture of public benevolence. He speaks of neighborliness and borrowing cups of sugar, and of the playground he says that children of all races, colors, and creeds will learn to live together in harmony. A week later, some of us are swatting flies on the playground’s inadequate little ball field. A gang of Negro kids, pretty much our own age, enter from the other side and order us out of the park. We refuse, proudly and indignantly, with superb masculine fervor. There is a fight, they win, and we retreat, half whimpering, half with bravado. My first nauseating experience of cowardice. And my first appalled realization that there are people in the world who do not seem to be afraid of anything, who act as though they have nothing to lose. Thereafter the playground becomes a battleground, sometimes quiet, sometimes the scene of athletic competition between Them and Us. But rocks are thrown as often as baseballs. Gradually we abandon the place and use the streets instead. The streets are safer, though we do not admit this to ourselves. We are not, after all, sissies—that most dreaded epithet of an American boyhood.

Item: I am standing alone in front of the building in which I live. It is late afternoon and getting dark. That day in school the teacher had asked a surly Negro boy named Quentin a question he was unable to answer. As usual I had waved my arm eagerly (“Be a good boy, get good marks, be smart, go to college, become a doctor”) and, the right answer bursting from my lips, I was held up lovingly by the teacher as an example to the class. I had seen Quentin’s face—a very dark, very cruel, very Oriental-looking face—harden, and there had been enough threat in his eyes to make me run all the way home for fear that he might catch me outside.

Now, standing idly in front of my own house, I see him approaching from the project accompanied by his little brother who is carrying a baseball bat and wearing a grin of malicious anticipation. As in a nightmare, I am trapped. The surroundings are secure and familiar, but terror is suddenly present and there is no one around to help. I am locked to the spot. I will not cry out or run away like a sissy, and I stand there, my heart wild, my throat clogged. He walks up, hurls the familiar epithet (“Hey, mo’f—r”), and to my surprise only pushes me. It is a violent push, but not a punch. A push is not as serious as a punch. Maybe I can still back out without entirely losing my dignity. Maybe I can still say, “Hey, c’mon Quentin, whaddya wanna do that for. I dint do nothin’ to you,” and walk away, not too rapidly. Instead, before I can stop myself, I push him back—a token gesture—and I say, “Cut that out, I don’t wanna fight, I ain’t got nothin’ to fight about.” As I turn to walk back into the building, the corner of my eye catches the motion of the bat his little brother has handed him. I try to duck, but the bat crashes colored lights into my head.

Moving on to the Dorchester neighborhood in Boston, Boston University professor Hillel Levine and Boston Globe journalist Lawrence Harmon, did a detailed history, based on hundreds of newspaper articles and interviews, on how that neighborhood went from all Jewish to all black in only a few years. A city initiative to increase mortgage access to blacks, lead to thousands of black families moving into Dorchester. Some residents fled immediately, others tried to be welcoming. But overall, there was an incredible amount of violence. Here are some excerpts from their book The Death of a Jewish Community:

Back in 1963 the Bernsteins and their two young children had outgrown their small North Dorchester apartment. It seemed logical to move a few blocks south to more expansive but still familiar Mattapan. Their two-family home on Ormond Street, near the top of the hill, provided a perfect balance between urban life and more pastoral pleasures. From the sun porch on the second floor, the couple could watch the bustle of Blue Hill Avenue. The pressures of the city, however, were easily forgotten when they retreated to their ample backyard for pleasant hours digging earth, spreading fertilizer, and planting grass seed. The Bernsteins thought they had it all. While just a stone’s throw from the Jewish shops and meeting places along the Avenue, they could still walk out their front door and be greeted by the lovely fragrance of their lilac bushes. Sumner Bernstein, a longtime city worker, had never put much stock in suburban master plans. For Bernstein, like thousands of other Mattapan residents, it was more important to have a ground floor apartment available for the comfort and security of aging parents.

On warm evenings the Bernsteins could be found sitting in their walkways on chaise lounges, nursing drinks and gossiping with friends. Janice Bernstein was a classic balabuste, a heavyset, energetic housewife with seemingly endless warmth and energy for her own family and the scores of neighborhood youngsters who passed through her kitchen.

…

It was while hanging out her laundry on a balmy summer day in 1967 that Bernstein overheard a neighbor, Jack Vetstein, discussing the formation of a new community group, the Mattapan Organization. Street crime had been increasing in recent months. Neighbors attributed the rise in purse snatchings and housebreaks to the movement of poor black families out of renewal areas in Roxbury into North Dorchester. Bernstein was discomforted by the conversation. She had lived on an integrated street in Dorchester and had little patience for those who sought to lay the world’s problems at the doorsteps of blacks. Like many of Boston’s Jews, she was familiar with the sting of antisemitism; it required only a small leap of her imagination to put herself in the place of an average black working family. She was wary, therefore, when her neighbor spoke of the need to prevent panic sales as blacks continued to seek housing further south down the Avenue. She felt more optimistic on learning that newly arriving black families also had shown interest in the fledgling Mattapan Organization and that the group was sponsored by religious groups in the area.

Unfortunately, as the neighborhood and the local school continued to transition, problems of crime and disorder became worse. The children her school went to – the Lewenberg – became infamous throughout the city for its disturbances. Janice Bernstein went from “baking cakes for her new black neighbors” to chasing their children with bats:

Throughout 1969 a school day [at the Lewenberg] rarely passed without violence or mayhem. City editors hungry to fill gaping holes in the newspaper knew that they could always pick up a story at the Lewenberg. On average, a reporter’s two-hour-long meandering in the Lewenberg revealed three fist-fights, a cafeteria food fight, a superficial injury to a teacher, and a host of exasperated quotes from shell-shocked administrators. None, however, ever reported that most rumored Lewenberg event: the sight of students hanging upside down from windows twenty feet above the schoolyard.

…

The mayhem was not confined to school grounds. At the end of the school day, the Lewenberg open-enrollment students burst down Wellington Hill toward Blue Hill Avenue. Nothing, it seemed, was safe along their path — tricycles were smashed and carefully planted rows of flowers were tramped upon; those unlucky enough to get caught in their path were fortunate to escape with just a shower of verbal abuse. Along the Avenue, vendors scurried to remove their goods from sidewalk stalls and dropped their iron grates before the Lewenberg wave broke over them. Those who moved too slow could expect to spend the next few hours salvaging fruit from overturned carts or trying to match left shoes with right.

…

Throughout 1969 the blockbusting of Mattapan and the crisis at the Lewenberg were taking their toll on Janice Bernstein. Once the first to arrive at the door of new neighbors with a platter of fruit, she had recently taken to walking the streets of her own neighborhood with her son’s Louisville Slugger baseball bat. Bernstein was particularly enraged by the school dropouts who had taken to lounging on the lawns in front of homes on Ormond Street and Outlook Road. The loud radios and litter were a constant annoyance to the homeowners. Requests to move off their property were generally met with profanity and insults. Calls to police assured nothing more than window breaking and increased harassment.

Like many white parents with children still at the Lewenberg School, Bernstein had taken to carpooling with friends: extortion and assaults had become too common to allow children to walk home from school. When it was Bernstein’s turn to drive, she frequently pulled up at a popular hamburger joint on Blue Hill Avenue at the foot of the hill where the kids could grab an afternoon snack. While waiting in the car for her son on a spring day in 1969, Bernstein noticed that he was being jostled as he stood in line for his milk shake. Three black youths, only a year or two older, bumped Bernstein’s son from side to side as he walked out to the parking lot. One assailant kicked the boy in the buttocks; amused, the other two quickly joined in. Bernstein had tried to teach her children self-reliance, but she was suddenly seized with a terrible fear that the incident would escalate beyond a schoolboy fight. Instinctively, she grabbed for the baseball bat at her feet and dashed toward the youths; they were at first startled and then amused by the large, red-faced woman, bat at the ready, who jumped from her car swearing and sputtering. Bernstein slowed her pace a few yards from the youths and raised the bat above her head. She remembers seeing red, literally: the three taunting youths appeared to be standing in a strange crimson glare. She was swearing heavily but felt a strange calm. “Come over here, you,” she called to each in turn. “Come over here.” The youths stood their ground, smiling inanely. “Stay there, then,” she said softly. “Just stay there.” Bernstein edged forward. She knew that the moment she was in reach of the first youth who had kicked her son she would take a full swing at him. Although the bat was still above her head, she could see the swing, could feel it connect. At that moment her gaze locked with that of one of the youths. The sight of the overweight housewife with the Louisville Slugger was no longer amusing — she had murder in her eye. The youth broke the spell and fled out of the parking lot onto Blue Hill Avenue, his companions right behind. Bernstein gave chase, sweat soaking through her dress. Long after the youths were out of reach, she continued the chase; Janice Bernstein, the welcome wagon lady on Wellington Hill, wanted to hurt someone.

…

If the blacks came to generalize Jews as slumlords, the Jews, particularly the elderly, perceived the black newcomers as violent criminals. Unsupervised youths cut a swath through the neighborhood and stunned the elderly Jews with the callousness of their crimes. A purse snatching on the Avenue was regularly followed with a knockdown and a sharp kick to the face. With the growing demands for black power and community control, many young black hoodlums fancied themselves as freedom fighters. An assault on an elderly pensioner was elevated to an attack on capitalism itself. Beating an old man on his way to an evening service at one of the Woodrow Avenue shuls and then yanking his pants down around his ankles translated as payback for hundreds of years of humiliating servitude. By 1966 the conversation at the G& G [Deli] was slowly turning from local politics to hospital updates for the latest mugging victim.

…

Stone listed crimes against Jewish residents and business owners, including the recent shootings of two drugstore owners and a fellow dentist. “The elderly Jews live in fear for their lives and they are not wrong,” Stone wrote. “I know because my office is in Dorchester and I have to repair their broken teeth. I see the closing of the drugstores because of firebombings and severe beatings of the owners… When I see these bumper stickers ‘Save Soviet Jewry,’ I can’t see why we don’t give out stickers to ‘help Mattapan Jewry.’ I feel they are just as bad off and a lot closer to home.”

…

In recent weeks scores of elderly Jews had been beaten and one had been shot. Each week an average of thirty elderly Jews in the neighborhood suffered assaults or robberies. Many knew of neighbors who no longer left their homes, not even to attend the morning or evening services required of the observant.

Moving on to Chicago, a writer describes how his wife’s family once tried to make a stand for integration – and failed:

As late as 1966, Austin [a working class neighborhood of Chicago] was all-white, with so little crime that my future wife walked a mile to first grade with her third grade sister every day. After school, the sidewalks of this neighborhood of three story condominiums were packed with children out playing while their mothers made dinner. (These days, when kids are chauffeured everywhere by their parents, the old Austin sounds like it was a paradise for both children and parents.)

After World War One, most blacks in Chicago had been restricted by chicanery and violence to living in a small, densely populated district on the South Side. This complete segregation broke down in the late 1950s. And then the increase in welfare payments in the progressive Illinois of the 1960s brought up from the rural South a lower class of blacks.

When Austin started to integrate around 1966, many of my in-laws` friends told them to sell out as soon as possible, before the neighborhood went all black.

But, as good liberals, my in-laws stood up for integration. And the first blacks moving in were middle class. So, they joined an anti-tipping liberal group of neighborhood home-owners started by fellow musician Father Edward McKenna—a composer who has written a couple of Irish-themed operas with librettos by Father Andrew Greeley. Members swore to each other they wouldn’t sell no matter how black the neighborhood got.

Well, the crime rate, which had been non-existent when the neighborhood was all white, started to soar. Housing prices fell, and soon the middle class blacks were selling out because underclass blacks were moving in. The members of the pro-integration group started to break their promises and move out. My in-laws stuck with their vows. But, then in 1968, rioters looted all the stores in the neighborhood after Martin Luther King was murdered. (My future wife called her mother to the window: “Hey, Mom! Look—free TVs! Let`s get some!” Her mother sent her to her room). And their small children, my future wife included, were mugged three times on their street.

So, my in-laws finally sold, losing about half of their life savings. They bought a farm 65 miles out of town, where they didn`t have indoor plumbing for their first two years of fixing it up.

Moving on to Detroit, journalist Ze’Ev Chafets, who grew up in Detroit and wrote the excellent first-hand account Devil’s Night, reports that the riots of 1967 destroyed a Jewish community of 80,000 people almost overnight:

When I left for Israel in the summer of 1967, the majority of Detroit’s eighty thousand Jews were clustered in the northwest corner of the city. Dozens of synagogues, religious schools, community centers and delis dotted the areas’s main commercial avenues, and families lived in spacious brick homes built along quiet, tree-lined streets. But the riot touched off a mass exodus; six months later, when I came home for a visit, I literally didn’t recognize the place. Not a single one of my friends’ families was still there.

More would exodus in the next year. The white population fell from 1,182,970 in 1960 to 413,730 in 1980. The number homicides rose from 125 in 1964 to 389 the year after the riots to 714 in 1973.

Moving on to Washington DC, in 1954 the Supreme Court’s Bolling decision forced the school system to adopt a desgregation program. The result was a tremendous amount of friction in the schools – friction based on behavior, norms, language, and due to gaps in where the students were academically. As a result of the friction, many of the white familes of means withdrew their kids from the DC school system. This is a pattern that would repeat across the country. Historian Raymond Wolters recounts the story in The Burden of Brown: Thirty Years of School Desegregation:

Desegregation got off to a good start in Washington, although its first days were not without incident. There was a two-day student strike at McKinley High School, where whites complained about blacks cursing and requesting the telephone numbers of white girls….

Beneath the general tranquility all was not well. Many of the problems that beset the District’s desegregated schools were brought to general attention in 1956 when a congressional subcommittee, a majority of whose members were southerners, investigated the situation. Spokesmen for the NAACP warned that there was “a real danger” of “a scurrilous attack … on Negroes of Washington and the process of desegregation”; they characterized the inquiry as a “preconceived” sally by men who believed from the start that desegregation was a catastrophe.

The investigators’ motives may have been questionable, but testimony given by more than fifty Washington teachers and school administrators nevertheless pointed to grave problems. The investigators may have run advance checks to find witnesses who would confirm the case against desegregation, but, as even the liberal New Republic acknowledged, the disturbing evidence that came out during the hearings is not made less disturbing merely because of the prejudice and ulterior motive of … Southerners."

The black students’ use of vulgar language bothered many whites. John Paul collins, who had worked in the District’s schools for thirty-four years and had been principal of Anacostia and Eastern high schools, declared that he “heard colored girls at the school use language that was far worse than I have ever heard, even in the Marine Corps.” Eva Wells, the principal of Theodore Roosevelt High School, believed vulgar language was the greatest cause“ of fights at her school. She said that ”so many remarks" had been made to Roosevelt’s girl cheerleaders during the basketball season of 1954 that it had been necessary to switch to boy cheerleaders the next year.

Nor was vulgarity confined to language. Arthur Storey, the principal at McFarland Junior High school, testified that in crowded corridors “boys would bump against girls” and “put their hands upon them but discipline was difficult to administer because ”a boy could say, ‘I was pushed.’ White girls at Anacostia High School complained about “being touched by colored boys in a suggestive manner when passing … in the halls,’, and the situation at Wilson High School got to the point where the student newspaper, The Easterner, published an editorial under the title ”Hands Off."

Admitting that the decorum of students left something to be desired even before desegregation, Dorothy Denton, a teacher at Barnard Elementary School, said that behavior was “going from good, or medium-good, to bad, in my opinion.” John Paul Collins said there had been “more thefts at Eastern [High School] in the last two years than I had known in all my thirty-odd years in the school system.”

When it came to disciplinary policies, many teachers believed they faced a difficult transition. Hugh Stewart Smith of Jefferson Junior High School said that before desegregation white teachers expected students to “do the right thing because it was the right thing to do.” Most black teachers, on the other hand, were said to insist on “rigid discipline,” for they had more experience dealing with children who thought that you got what you wanted by fighting.“ Katherine Reid, a veteran white teacher at the Tyler School, admitted that she initially found it ”very hard to make colored children do what I told them.“ One day when she was having trouble with a black girl, ’one of the colored boys said, ‘Miss Reid, why don’t you stop talking to her and bat her over the head the way her last teacher did?’”

Some teachers said their authority had been undermined. Katherine Fowler, who taught at McKinley High School, had an unpleasant experience after she scolded black students who were singing in the hall and disturbing others. The students said she was picking on them because of their race. An official of the NAACP discussed the matter with Fowler’s principal, who warned the teacher to “be careful” in disciplining black students.

One teacher expressed the view of many of her colleagues when she said she was “shocked at the low achievement of the Negro children who have been in the schools of Washington.” In twenty-two pre- dominantly white elementary schools the average I.Q. was 105, while the average in predominantly black schools was 87.

Whatever the cause of the low scores, classroom teachers clearly were confronted with serious problems associated with teaching students of varying abilities in the same class. Ruth Davis, a veteran teacher with 41 years’ experience in the classroom, said it was difficult to teach when students of widely varying abilities were placed in the same classes. “It was hard on everyone concerned. It was hard on the boys and girls who needed the special help. It was hard on the ones who could have gone ahead. And it was very discouraging for the teacher who had no means of serving every one.” Helen Ingrick of the Emery School also found teaching “very difficult, because you had to have so many groups and so many age levels and so much preparation for the different range of abilities.” Dorothy Denton of the Barnard School thought that her better studenrs were suffering educationally because she had “to put so much time on discipline and on low ability that I haven’t the time to give to the children who are able to go on.” After nine days of testimony, the congressional subcommittee concluded, “The evidence, taken as a whole, points to a definite impairment of educational opportunities for members of both white and Negro races as a result of integration, with little prospect of remedy in the future.” The subcommittee recommended that the schools be formally resegregated, but its chairman, James C. Davis of Georgia, predicted that even if this were not done the departure of whites and the immigration of blacks would accomplish the same end – segregated schools.

…

After the Bolling decision, the rate of white withdrawal from the public schools tripled. Between 1949 and 1953 white enrollments had declined by about 4,000 students; between 1954 and 1958, white enrollments declined by almost 12,000 students. The District abandoned segregation, but white parents and students then abandoned the District.

In Boston in 1974 a federal judge ordered busing to fix racial imbalances in the school system. There was terrible violence on both sides, with many of the whites leaving the district. Ultimately, the schools were more racially imbalanced than they ever were before the court order:

Many parents, and a few students, also wrote to Judge Garrity telling him of assaults or harassment: the fifteen-year-old junior on her own attending classes at Roslindale and South Boston who found it difficult to pay attention because of constant tension, who did not regard herself as prejudiced, and who found it trying “when I’m told (in exact words) ‘I’m gonna’ kick your ass, bitch,’ when I’m just minding my own business” and racially motivated harassment kept on; the Roslindale father who described the Philbrick School as racially imbalanced with more blacks than whites, with blacks given preferred treatment (“ let’s keep peace”) while white children were unsafe going to restrooms and in the school yard, with blacks not allowing whites to participate in games, white children ganged up on, in his view the “school totally taken over by blacks”; the Hyde Park antibusers and parents who lamented the racial attack on seven “of the outstanding 10th graders” at Rogers Hyde Park Annex who had now left the school; the West Roxbury mother of a fourteen-year-old boy beaten by two blacks wanting a quarter, the day after he missed school because the bus did not show up, “no explanation, therefore no school”; the Hyde Park mother whose daughter’s bus was stoned by blacks and who now suffered from nightmares and other emotional upsets; the West Roxbury parent whose five children had already attended the Shaw School, now majority black, whose sixth, an eleven-year-old, had known many anxious mornings and had now been assaulted twice; the Dorchester father whose boy was attending Dorchester High, which instead of being 52 percent white was 65 percent black, and which would soon be 70 to 80 percent black, where a black “in jest” pulled a knife on his son and was told to put it away by a black aide, where his son and two others had their pockets emptied by blacks during a fire drill; and the Boston father whose daughter came home needing three stitches in the back of her head.

Several parents repeated the theme that “it’s common knowledge that the lavatories in some of these schools are manned by young toughs who demand money from kids that have to use them.” “I don’t care what color my kid is sitting next to,” wrote one Roslindale mother, “as long as he gets the education … . I’m willing to work at living together in peace and harmony but I don’t want my kids hurt in the process.”

…

[From another letter to Judge Garrity:] “I was borned [sic] in Roxbury on Blue Hill Avenue 40 years ago. A person would either happen to be insane or want to commit suicide to travel in that area today. I moved to Mission Hill… when I started High School. To me, that was God’s little acre until the projects, two (2) behind the church and one (1) in Jamaica Plain, became non-white. When I was living there, there was no such thing as locked doors or being afraid to walk the streets at night … . Now the priests are warning the old people not to come to daily mass because of rampant crime … i.e., muggings, stabbings, etc. My parents still live in fear with double and triple locks on their doors.” (Boston Against Busing, p. 183)

In city after city the firsthand accounts show that the violence came first. It was the violence that caused white people to leave the city so rapidly.

On White Violence and Urban Decay

In recounting the above stories of black-on-white violence I do not mean to deny the existence of white-on-black violence. The stories you have heard in the mainstream histories almost all happened. In Boston the people of Southie violently resisted integration in schools and housing:

The first day of school in September brought scattered violence that continued throughout the week…a black reporter from out of town drove into Southie and was assaulted. Throughout the city buses were stoned, cars overturned, and in the worst incident, seventy-five white youths stormed into Bunker Hill Community College in Charlestown, trashed the lobby, and sent a black student to the hospital. (Boston Against Busing)

Distressed by the refusal of white working-class Bostonians to support its challenge of de facto segregation, the NAACP, for the first time, entered the South Boston parade. Its float bore a large portrait of the recently assassinated John Kennedy and beside it, in bold green letters: “From the Fight for Irish Freedom to the Fight for U.S. Equality.” As it lumbered onto Dorchester Street near St. Augustine’s Church, four teenagers leaped into the street brandishing their own homemade banner, decorated with shamrocks and reading: “Go home, nigger. Long live the spirit of independence in segregated Boston.” Tomatoes, eggs, cherry bombs, bottles, and beer cans rained down on the float. A brick shattered the windshield and broke the driver’s glasses. Police moved in, escorting the float to safety. The next day, the NAACP likened the incident to “the viciousness you would expect in New Orleans and the backwoods of Mississippi.” (Lucas, Common Ground)

When a black family moved into the edge of white Southie, there was a series of fights, and attacks on the house:

Over the next two months, Olbrys and Kennealey made more than a dozen arrests around the house. On one occasion, lurking behind a tree, Kennealey saw a youth cock his arm as if to throw. The detective seized the kid’s hand, extracted a rock, and placed him under arrest. Some nights later, after a black Plymouth circled the Debnams’ house with three youths shouting, “No more fucking nig*ers!” Olbrys stopped the car and arrested its occupants. That weekend, he apprehended four kids who had thrown beer bottles against the front porch.

But despite the detectives’ diligence, the culprits rarely received much of a sentence. None of them ever spent a night in jail. The most celebrated incident occurred on September 10, a lively night around the Debnams’ home. Shortly before 1: 00 a.m., a firebomb exploded in the driveway, scorching the family car. Three hours later, two figures were seen prowling the yard with a pistol, shouting racial epithets and ultimately firing one shot toward the house. The detectives arrested Fred Gavin, nineteen, and his brother John, eighteen. Originally, both boys were charged with assault with a deadly weapon, and Fred with illegal possession of a gun. But the assault charges were quickly reduced to disorderly conduct. Finding John guilty, Judge Dolan gave him a three-month suspended sentence. He found Fred Gavin guilty of disorderly conduct and illegal possession, which carried a mandatory sentence of one year in prison. But on appeal in Superior Court he was acquitted of both. (Lucas Common Ground)

And here is a story from Boston’s Charlestown: